How to Commit Brandicide

What UnitedHealthcare and WPP Have in Common with Tesla

Brands are basically a promise. They’re also a form of soft power.

They are a tool for persuasion in the “battle for your mind” (to quote Al Ries and Jack Trout), positioned to wheedle their way into the collective subconscious of a market. A brand tells people how they should think and feel. And branding is a way of showing personality. Businesses, and increasingly governments, invest big bucks on the image of their brands to create preference (estimated branding spend by top 100 public companies in the past year: $36–73 billion). One way of measuring strategic success or failure is the NPS, the Holy Grail of Satisfaction.

Brand China, for example, is on the ascendant.

Chinese technology, blockbuster video games and popular consumer brands are boosting the country’s image abroad, the government’s executive management intentionally building soft power in order to help with its hard power. It wants to influence not only future consumers, it wants to influence future world leaders and voters so that there are more bills and policies that benefit China’s rise.

The country is basically becoming cool, say Jiehao Chen, The Economist’s China researcher and Gabriel Crossley, its China correspondent, in Brand China is having a moment, a podcast last month. “There are surveys which show China’s brand is definitely on the up, especially among young people. A Danish NGO called the Alliance of Democracies Foundation showed that China’s net perception is now plus 18%, which isn’t too high, but it’s a lot higher than it used to be.”

Meanwhile, Brand America is on the descendant.

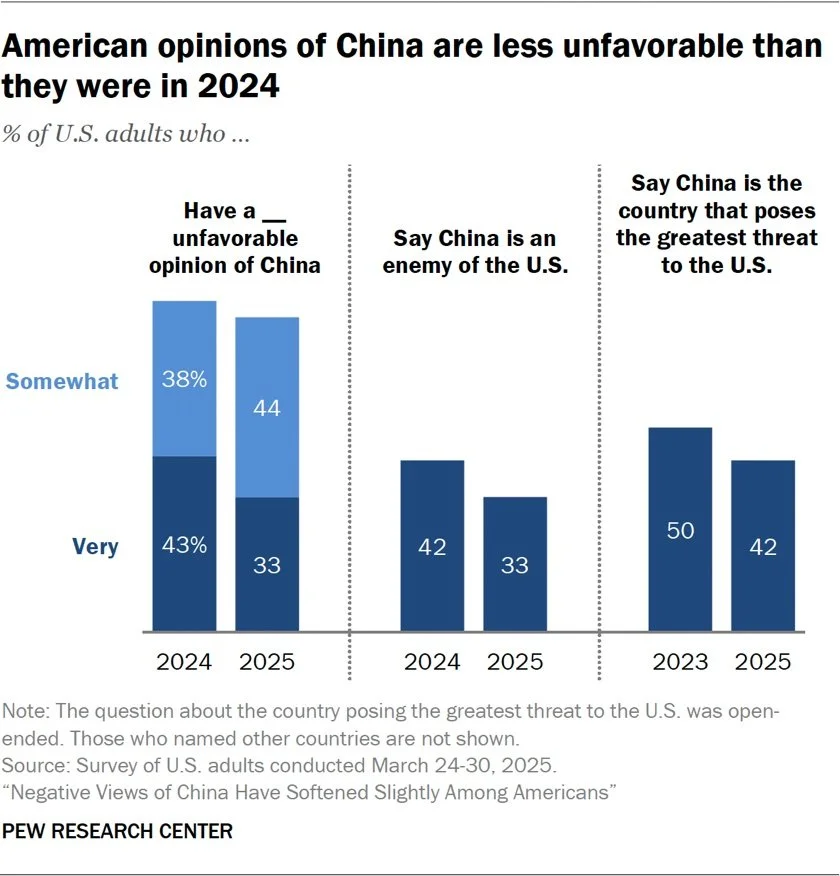

A Pew poll in April showed that, for the first time in five years, the share of Americans with an unfavorable opinion of China has fallen from the year before, from 81% in 2024 to 77% in 2025. Another poll by Axios shows that by the end of May, China had also overtaken America in net favorability.

Brand China is Cool

For the first time in five years, the share of Americans with an unfavorable opinion of China has fallen from the year before

The unfolding strategic collapse in America's ‘brand value’ is already costing the country big economically — foreign visits into the United States fell off a cliff last quarter (down roughly 20 percent), visitors turned off by White House policies. The strategically-collapsing brand value of The Dollar (tumbled almost 11% against its global peers through June) has JPMorgan seeing its hegemony come into question due to plate tectonics, geopolitical and geostrategic shifts. As a result, de-dollarization has increasingly become a substantive topic of discussion among investors, corporates and market participants more broadly.

“The concept of de-dollarization relates to changes in the structural demand for the dollar that would relate to its status as a reserve currency. This encompasses areas that relate to the longer-term use of the dollar, such as transactional dominance in FX volumes or commodities trade, denomination of liabilities and share in central bank FX reserves,” said Luis Oganes, head of Global Macro Research at J.P. Morgan.

Importantly, this structural shift is distinct from the cyclical demand for the greenback, which is shorter term and has in recent times been driven by U.S. exceptionalism, including the relative outperformance of the U.S. equity market. “The world has become long on the dollar in recent years, but as U.S. exceptionalism erodes, it should be reasonable to expect the overhang in USD longs to diminish as well,” Oganes said.

The original idea of soft power, as the late Joseph Nye would have had it, is that it’s supposed to be organic. It’s like the private sector and civil society are what makes a country likeable, not the government.

The Economist’s Crossley on the rise of China’s NPS: “So if you combine the cool technologies which China does seem to be coming up with in last couple of years, everything from electric vehicles to video games to DeepSeek, and then you combine it with some of these changing poll numbers, it suggests that people are thinking about China in a different way.”

They’re also thinking about Tesla in a different way.

Musk Commits Brandicide

Elon Musk is Exhibit A in how to commit Brandicde. He not only squandered the opportunity to sensibly reform government. His antics have ruined the reputation of electric vehicles, says Francis Fukuyama, an American political economist best known for his book The End of History.

The accolades that were piled on him before he ventured into politics were well-deserved. Tesla created a new category of industrial product, an entirely new industry ecosystem, and out of nowhere became a serious car company; SpaceX is the backbone of the American launch industry, another new economic system the Visible Hand of Musk shaped almost from scratch; and Starlink has proven its worth on the battlefields of Ukraine.

But things have gone off the rails for Brand Musk.

Fukuyama in The Tragedy of Elon Musk, a recent Substack:

The tragedy for U.S. politics is that Musk may have destroyed his one outstanding creation, Tesla, by his misguided foray into politics.

The first thing they will teach you in business school is not to politicize the products you want to sell to the general public. Blue-leaning voters were his company’s biggest fans; every other car in my very liberal neighborhood in Palo Alto is a Tesla. Trump’s MAGA base is unlikely to shell out big bucks for an electric vehicle, a product category that Trump himself has trashed. The Chinese are building very competitive models far more advanced than Tesla’s aging product line, and legacy car companies are catching up.

Musk’s poor political judgement has led to a doubly terrible outcome: he and DOGE have done great damage to the U.S. government, and his neglect of Tesla while he detoured into politics make its very survival as a company questionable.

If Tesla fails, the country as a whole will suffer. The United States needs to show that it can still innovate in industries that require bending metal, something that hasn’t happened much in recent years. Tesla was leading the transition to a low-carbon future, and making money off of it. That future may now belong to China, whose EVs by all accounts are world-beating.

How bad is the train wreck?

Tesla’s revenue drop is calamitous. The number of vehicles sold fell 81% year-on-year in April in Sweden and 73.8% in the Netherlands, with steep falls in Denmark, France, and the UK, despite demand for electric vehicles going up. The US saw a smaller but still noteworthy fall, Inside EVs reported. Europe is a particular issue since Tesla opened a “gigafactory” in Germany in 2021, capable of building 375,000 cars annually but “likely to be underutilized for some time,” Ars Technica reported. Competition from China is part of the problem, but Musk’s embrace of right-wing politics also appears to be toxic to many EV buyers.

Tesla’s dominance in California — the largest electric vehicle market in the U.S. — is crumbling: it posted a seventh consecutive quarter of declines in new vehicle registrations even as major competitors like Toyota and Honda saw robust growth, according to data in the California New Car Dealers Association Q2 Auto Outlook. And yesterday, Tesla reported its biggest decline in quarterly revenue in more than a decade. Musk warned of "rough quarters" ahead.

UnitedHealth’s Campaign to Quiet Critics is a thin piece of journalism from the New York Times last week that detailed UnitedHealthcare’s hard power tactics to ward off disruption, the primary responsibility of the people who manage big systems. It describes how the brand is engaged in "an aggressive and wide-ranging campaign to quiet critics. In recent months, UnitedHealth has targeted traditional journalists and news outlets, a prominent investor, a Texas doctor and activists like Ms. Strause and her father, who complained about a UnitedHealth subsidiary. In legal letters and court filings, UnitedHealth has invoked last year’s murder of Brian Thompson, the chief executive of the company’s health insurance division, to argue that intense criticism of the company risks inciting further violence."

The counter attack shouldn't surprise.

Economically complex UnitedHealthcare is the subject of extensive investigative reporting from many publications into its billing practices and denials of patient care. It faces a variety of federal criminal and civil investigations, including into potential Medicare fraud and antitrust violations. And so UnitedHealthcare will defend itself following its industrial logic, a mode of being and seeing and thinking….an entire knowledge system….that began in 1977, when Charter Med Incorporated was reorganized under the brand name United HealthCare..

The brand is at a tipping point, trying to navigate the tension between rot and genesis. The moment demands a Big Defense against the many barbarians at its gate. It would almost be professional malpractice to do otherwise.

“Negative publicity may adversely affect our stock price, damage our reputation and expose us to unexpected or unwarranted regulatory scrutiny,” UnitedHealth noted in its most recent annual report. Memo to the board of UnitedHeatlchare: that damage has already been done. The company’s shares have declined 40 percent over the past year, translating to about $190 billion in lost market value, and UnitedHealth Group currently has a Net Promoter Score of around –12, based on data from May 2025. This is significantly below the healthcare average (+38 to +58).

Eric Hausman, a spokesman for UnitedHealth, defended the company’s tactics in a statement to the Times. “The truth matters, and there’s a big difference between ‘criticism’ and irresponsibly omitting facts and context. When others get it wrong, we have an obligation to our customers, employees and other stakeholders to correct the record, including by making our case in court when necessary.”

A directionally correct statement, as these kinds of statements always are.

But you’re also not going to be able to rebuild the clanking machine of UnitedHealthcare, and by extension the American Way of Healthcare, into an engine of Big System Competition (and advantage over China), with that obsolete storyline of value. The words have run out of juice. They lack kinetic energy. They do not persuade. They do not have the compute power to stop a runaway process, the giant feedback loop that is now in control of UnitedHealthcare’s fate as a brand.

Hell Sucks

Every Big System is its own self-causing agency — it self-generates itself around a theory of performance that everyone “knows” to be correct based on past experience and expertise, not to mention education, even though that education is itself root cause. The biggest gap in the curriculum? Teaching that markets can implode.

Rethinking Economics recently took stock of the state of economics taught at UK universities in its 'curriculum health check'. The findings are sobering. "The climate crisis and socio-ecological issues are broadly absent from economic curricula," it found. The report shows how the mainstream's best-ranked universities often perform the worst in preparing students for the real world, writes Ha-Joon Chang, who teaches at Soas, University of London today in the Financial Times. "We are training future economists to fail again.

An embedded economic system is really more of a giant feedback loop; it is the cause and effect of itself, its own intrinsic order and organization. Think of feedback loops as an orbit of control, gravitational pull toward a stable point, a stasis, status quo. The Santa Fe Institute would explain all this as the inescapable second law of thermodynamics — that the future is just a shuffled version of the past.

Feedback loops are why you can’t “fix” an embedded economic system. Ever.

Which is why I agree with Martin Sorrell, the founder and former CEO of WPP, who said last week that Brand WPP may be “too far gone” for incoming chief executive Cindy Rose to turn around the business.

Speaking to Campaign, he said, “Cindy Rose’s operating experience at Disney, Vodafone and Microsoft may be stellar and she may be very talented, but the question is whether the business is too far gone as a result of the approach of the last seven years and would be better off being dismembered into its still-standing constituent parts or consolidated elsewhere."

“WPP has spent over £1.5 billion over the last five years below the headline operating profit line on mostly cash restructuring charges and built up multiple levels of overhead at group, sub-group and company levels," he said. “Under the guise of simplification, the leadership has collapsed storied brands such as J Walter Thompson, Young & Rubicam, Wunderman, Grey, Hill & Knowlton, losing not only many talented leaders, but clients as a result, too.”

The market cap of rival Publicis is now four times the size of WPP, and WPP issued another profit warning for Q2, revising its full-year revenue forecast to a decline of between 3% and 5%.

Leaders have a hard time conjuring new narratives, and new growth curves those new narratives should inspire, because it’s easier to simply buy operational tweaks at the edges, to “optimize” the current operating model, the same one that’s been operating the same way for years, if not decades.

UnitedHealthcare, WPP and Tesla are not dealing with context to much as they’re dealing contextual collapse. Everyone is on the same rough rough ahead.

A new economic terrain has formed around us and within us at the same time. It is riddled with dead ends, trails that lead to false summits, and made impassable by big-time discontinuities. Because there is no certainty, a brand has no way of knowing whether it is heading up a slope toward a peak new market, or is actually climbing anything larger than a hill. In biological terms, a brand may succeed in getting to the top yet find itself stuck on a suboptimal peak.

Something Andrew Witty, Mark Read and Elon Musk learned the hard way.

/ jgs

John G. Singer is Executive Director of Blue Spoon, the global leader in positioning strategy at a system level. Blue Spoon specializes in constructing new industry narratives.