Healthcare, the Next Tom Brady and the Real Wealth of Nations

The strength of an embedded system is not in its action, but its staying power.

In the United States, the $4 trillion healthcare market is controlled + managed + protected by a handful of economic keystones whose power and gravitational pull have been developed over decades. In ecological terms, these are the 'apex predators' and they have deep pockets, wide moats and many weapons of mass entrenchment at their disposal -- the big boys, as they say, all carry Magnums.

Look no further than UnitedHealth Group to understand why healthcare is not fixable, at least not in its current configuration.

"UnitedHealthcare has internalized a critical fact about health care,” write Krista Brown and Sara Sirota in ‘Health Care’s Intertwined Colossus’, their excellent unpacking in American Prospect of how years of policy failures have created an industrial complex that is the very definition of a system advantage. “If you sit on every side of the transaction, from doctors to insurers, drug payers to drug prescribers, lifesavers to end-of-life carers, you not only grow as the system grows, but you have the ability to steer the entire system inside your gaping maw. Conflict of interest is really the business model,” say Brown and Sirota.

Today, UnitedHealthcare is the fifth-largest public company in the U.S., bigger than JPMorgan Chase. Its insurance products serve 50 million members, more than the population of Spain, and its $186 billion health services division, Optum, has 103 million patients, more than Vietnam’s population. Earnings came to $28.4 billion last year, putting it in the top 30 of companies worldwide.

UnitedHealthcare is a ‘control point’ with an economic moat that can’t be breached.

And healthcare's infinitely expanding ‘problem + solution space’ is too intertwined to cleanly cleave, much less cohere in way that makes sense. It's too big a thing to whip into a neat package sold with a simple PowerPoint, but sell we do, in under 20 minutes, at Shark Tanks with 10-slide pitch decks raising billions from venture capital funds. (In the first six months of 2023, U.S. digital health startups raised $6.1 billion across 244 deals, with an average deal size of $24.8 million, according to an analysis by Rock Health, a venture fund dedicated to digital health. While that $6 billion seems like a hefty amount of cash, that's down considerably from $10.4 billion raised in the first half of 2022 and an eye-popping $15.1 billion raised in the first six months of 2021.)

But you can’t tech your way to “fixing” healthcare, something Apple and Amazon (via Haven) learned the hard way. If anything, the fragmentation is only getting worse, not better. The psychic disintegration is overwhelming. And the blow-up-your-brain complexity explodes exponentially.

So our default is a kind of strategic drift: the ornamental wave of 'patient engagement' enabled by digital transformation — this is positioned and promoted as a big innovation agenda, made possible by a "brilliant diversity [of digital health and artificial intelligence projects] spread like stars, like a thousand points of light in a broad and peaceful sky".

And there is a large market for this galaxy of technology applications, UnitedHealthcare being one of them. Yet all the technical potential of what technology “can” do ultimately fails to scale in a meaningful way (a condition called “pilotitis”).

We remain stuck with structural stalemate, where new math from new data masquerades as novel strategic vision. Everything seems directionally right, but somehow stasis persists.

Healthcare, in other words, is working with a short-yardage offense when it should be opening up the game with the forward pass.

The New System Quarterback

The only way to "fix" the American Way of healthcare is assume you know nothing at the start, other than everything works and everything is broken and everyone has personal knowledge of the experience that needs correcting. We have all been to a doctor's office or visited a pharmacy, we have all dealt with government and commercial insurance plans. We are a nation of 300 million experts in healthcare.

Better to step off into a corner for a different review of reality, and then put in place a deliberate process of creative destruction. Bring pieces and parts together in a unique pattern, create a new bundle of knowhow, position outcomes at the center of thinking.

And the way to do this? You simply chop the knot.

Leapfrog an embedded economic system. Invent leverage from scratch. Reorganize markets to interoperate within the context of new economic systems. “We just need to start over,” Blue Shield of California Chief Executive Officer Paul Markovich said when explaining the logic for replacing some of its drug procurement services from CVS Health. (His view is echoed by economists Liran Einav of Stanford and Amy Finkelstein of MIT, in their new book “We’ve Got You Covered: Rebooting American Health Care.)

And as I wrote in Fortune, it's the right approach. It’s the competitive mindset that needs a big rethink.

“Unleashing exponential growth in the largest and most lucrative market on Earth starts by leapfrogging complexity. And if you buy into the logic that it’s not just one market that determines health care’s value but an infinite flow of them, then a strategic advantage goes to leaders with the skills to harness a number of interconnected markets and manage them as a new ecosystem.”

But simple doesn't mean easy.

At issue is a much deeper and wider set of feedback loops baked into a massive flywheel of dysfunction. It's become the defining feature of a global disfiguration: healthcare is "uneconomic" because of an obsession with cost and controlling spending on prescription drugs. Our solutions are not mind-stretching enough. The magic leap to "economic value" is made by reframing the game.

Start with the end result and work your way back.

And the 'new species' to make this big market shift happen — the “system quarterback” if you will (think Tom Brady and Peyton Manning) — are the employers generally, and the HR/procurement departments specifically.

“With Tom Brady, it was more about Bill Belichick and the entire team [as a system], the execution and them having a game plan. But something in the first quarter meant something totally different in the second,” said former New York Jets and Baltimore Ravens star Bart Scott in an interview on ESPN radio. For more on this, see "Tom Brady is a system quarterback and Peyton Manning is the system" - Shannon Sharpe explains the difference between the two QBs” here.

Employers are the only real payers in healthcare.

Everyone else — including UnitedHealthcare, including ExpressScripts, including Epic, including Merck, including Northwell Health, including Google, including Willis Tower Watson — is a vendor pitching for the employers’ business. They’re commodity inputs; differentiation happens through new system vision, by combining them in new ways, to force economic integration.

It’s this insight that is the equivalent of the forward pass in football. (Critics said its introduction in 1906 would doom the game by making it less physical.)

Employer leverage comes from managing their portfolio of health vendors differently — harness the carnival of vendors with a ‘system RFP’ that disrupts pitch behavior, forces vendors to cohere on the same “value framework,” collaborate with employers and then perform as a team. The objective is to create unique value for the employer’s business as a whole, not extract value from it as a ‘rent-seeking’ middleman leveraging administrative complexity as a form of cheap growth.

This is why Kraft Heinz is suing Aetna, claiming the insurer is not providing all of Kraft Heinz's medical claims data. More lawsuits of this sort are likely to come. From MedCityNews reporting (The Kraft Heinz Lawsuit Against Aetna Is the ‘Tip of the Iceberg’):

“These lawsuits are just the beginning of what’s to come, said Cheryl Larson, president and CEO of Midwest Business Group on Health, a nonprofit supporting employers.

“I’m concerned that if a company as big as Kraft Heinz is being cherry-picked, what’s happening to the rest of the employers in this country?” Larson said in an interview. “I can’t imagine that other healthcare stakeholders are ready for what is about to happen. … I think this is the tip of the iceberg.” Larson’s use of the phrase “cherry-picked” refers to insurers not providing employers with full access to their claims data, thus making it difficult for employers to complete full reviews of their health plans.

I think if there’s one piece of advice [I have], employers have to lean in to having really uncomfortable conversations right now,” Deacon declared. “I understand that they might have a 20-year relationship with their broker, they might have a 30-year relationship with their consultant, they might have a 10-year relationship with their TPA. Nevertheless, you have to lean in now to having really uncomfortable conversations to understand what’s what in the state of your health plan and then take swift action.”

If they don’t take these steps, then employers are at risk of being sued themselves by their employees for not fulfilling their fiduciary responsibilities.

You have to build a new foundation brick by brick.

This means elevating human resources strategically, arming them with a new pool of data, making them a partner with ‘the business’ and empowering them to behave exactly like the best quarterback to ever play in the NFL.

The Real Wealth of Nations

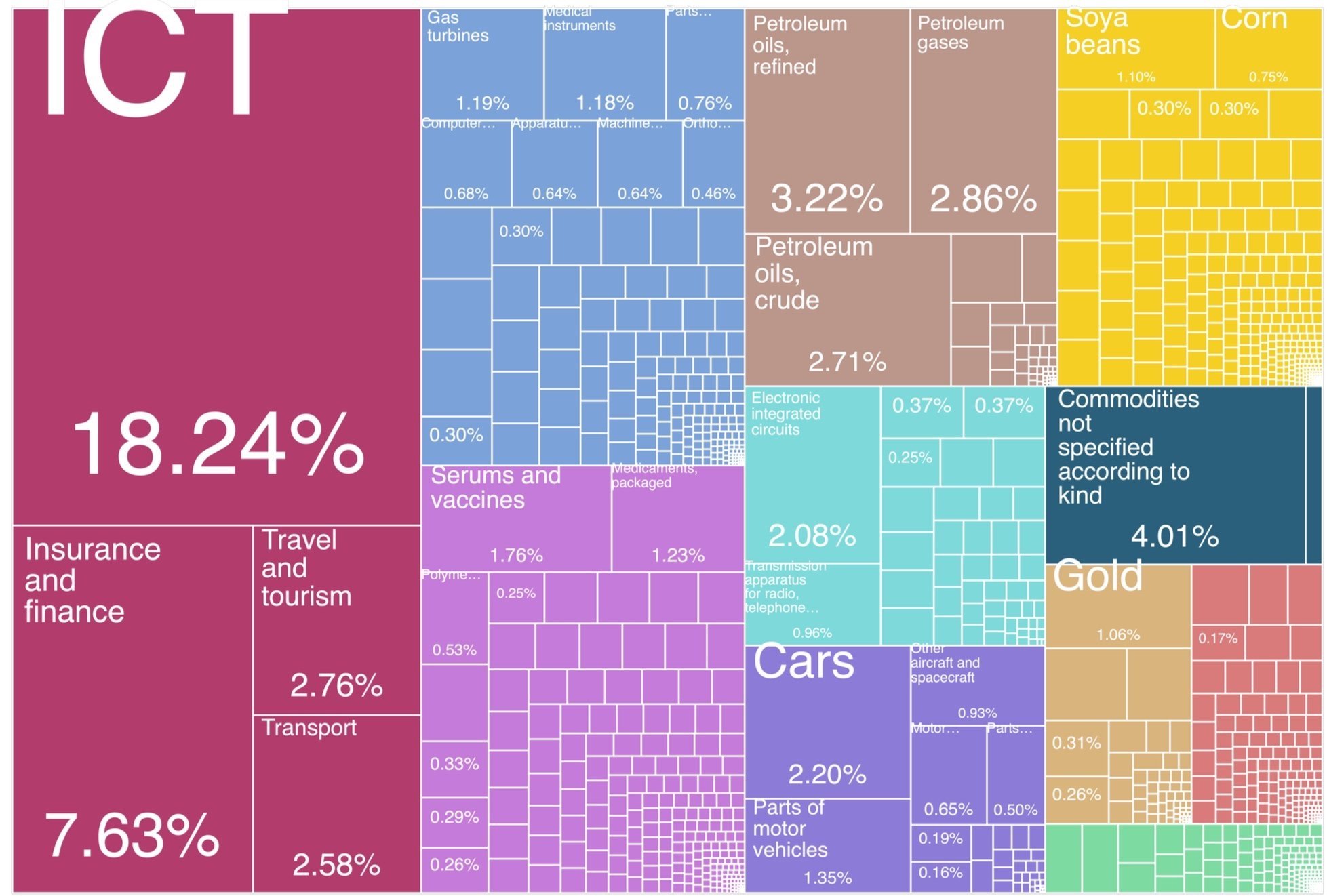

From the Growth Lab at Harvard is this tree map of the economic structure of the United States in 2021.

The Export Basket of the United States in 2021

The United States exported products worth USD $2.55 trillion in 2021 (imports totaled USD $3.48 trillion). At around 26 percent, Information and Communications Technologies (ICT) and Insurance and Finance markets dominate what the US makes, the source (real and perceived) of "innovation" as a growth driver, and strategic thinking about economic competition. Pharmaceuticals ("Serums and Vaccines") is less than 2 percent.

"During the past two centuries," write the authors of the Atlas of Economic Complexity, from which this data is drawn, "there has been an explosion of 'productive knowledge', by which we mean, the knowledge that goes into making the products we make. Expanding the amount of productive knowledge available in a country involves enlarging the set of activities that the country is able to do."

The US excels at specialization, the 'division of labor' that produces an infinite flow of products for individual consumption. But it fails spectacularly at the "productive knowledge" to produce health outcomes. We simply don't know how to change the pattern of interaction between markets, of combining the parts so that a new economic system is born. And so the United States is stuck in a weird dimension: having the best science and technology in the world but delivering rates of early death well beyond those of other rich countries. Writes The Economist last month:

"Horrifying numbers of Americans will not make it to old age

But on a more fundamental measure of wellness — how long people live —America is falling behind. To its detractors, this is a cause for schadenfreude. “Many people say it is easier to buy a gun than baby formula in the us,” gloated a statement released by the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs last year, which also pointed to declining life expectancy in general. In the past few years, according to some estimates, life expectancy in China overtook that in America. For Americans, that ought to be a more serious source of introspection than it is."

Where the logic of most "value frameworks" in healthcare gets fuzzy is in the Adam Smith framing. (For more on this, read my essay, AbbVie Leaves the Herd.)

We're comfortable sitting on the mental furniture of the past -- this is the easy chair of dogma and the fragmentary worldview. It's simple to divide things into parts, to assume-away complexity, and then manage separate activities separately, to small objectives. For example, controlling price of an input to health (e.g., drug products). But despite all energy and noise around drug pricing, the “price” of pharmaceuticals isn't the real problem. Not directly anyway. Neither, for that matter, is “cost”. That employers and workers are expected to see an increase of about 6.5 percent or higher in health-plan costs next year is but a symptom of something else entirely: a financial system that sees and measures “healthcare” as statistically separate and distinct from the rest of the economy, as a kind of background radiation.

The thing for industry + government to create collaboratively is a new map to prosperity that positions "healthcare" as the true Wealth of Nations.

Something like this:

The ‘Positional Value’ of Healthcare

If we learned anything in 2020, it should be that public health is not separate from economic health. “Healthcare" is the economy, a meta-market around which $142 trillion in global GDP is linked and flows. If you buy into that view, then the new growth engine ‘for an economy’ is the production of affordable health: the intentional design of entirely new economic systems where “healthcare” is positioned as a keystone to economic resilience and prosperity.

More to the point, the “future of wealth and growth” does hang in the balance, to quote McKinsey Global Institute’s marketing for its new ‘global balance sheet’ concept, but the new financial system to manage things should be constructed around this simple idea: healthcare is the economy.

This is about creative leadership with intention, strategy designed to break the loop in time in which the American Way of Healthcare is trapped. After more than 50 years, it's time for market innovation, at scale, a whole new economic narrative lead by employers.

From the review of Men, Money and Medicine in The New York Review of Books, published in 1970:

"The American crisis over health has finally taken a place alongside the urban crisis, the ecological crisis, and the “youth crisis” as the subject for solemn Presidential announcements, TV documentaries, and special features of magazines. But to the average consumer of pills, hospital care, and doctors’ services, the crisis in health care is nothing new, except that the stakes -- health, beauty, and life itself -- get higher with each advance in medical technology, from miracle vaccines to organ transplants.

The odds against the sick are high, and getting higher all the time.

Money aside, the consumer’s major problem is finding his way about an increasingly impersonal, fragmented, irrationally arranged set of health services. Fundamental improvements in healthcare can be achieved only through a head on confrontation with our political and economic system.”

We have become comfortably numb with the conversation.

Put another way, the conversation is hardly a conversation at all. It is a ‘nonversation’ that goes nowhere. The “model” does not develop or build on new interactions. It is not dynamic. And so structural stalemate becomes the defining feature of things.

Every Economy is a Healthcare Economy

Warren Buffett has it right when he said: “GM is a health and benefits company with an auto company attached.” In fact, it spends more on healthcare than steel, just as Starbucks spends more on health care than coffee beans. For most companies, healthcare is the second largest expense after payroll. “You run a healthcare business whether you like it or not,” says Dave Chase, founder of Health Rosetta.

Good policy today requires not just a ‘right analysis’ of the economic problem, but the right synthesis.

The “price” of pharmaceuticals is not the issue — the issue is working out a new general theory of markets that positions the ‘production of affordable health’ as an economic objective, where the basis of strategic competition is outcomes from new economic systems, not consumption of individual inputs. Yes, we need to reframe the conversation from election-cycle policies to generational policies with a long-term focus on getting better EBITDA from a $4 trillion investment. As any employer in any sector will probably tell you, “healthcare” is the real source of leverage, the foundation upon which everything, literally, sits.

A winning playbook starts with a different competitive mindset.

It’s less about one dimensional “piece vs. piece” competition, but playing a new, three-dimensional game with system vision, like Tom Brady. The goal is shifting the center-of-gravity for power and control, to see the ‘positional value’ of healthcare differently. To apply a concept from Harvard’s Growth Lab, healthcare is a Feasible Opportunity for strategic leadership by human resources and employee benefit teams.

The second quarter is about to begin.

/ jgs

John G. Singer is Executive Director of Blue Spoon Consulting, the global leader in positioning strategy at a system level. Blue Spoon specializes in constructing new industry ecosystems.