Why the Pharmaceutical Industry Needs to Think Like Quentin Tarantino

The elephant in the room is the room itself, an approach to business and product marketing unchanged since the “modern pharmaceutical industry” began around 1849, when Pfizer was founded in Brooklyn. The entire concept is the problem.

Updates since original publication on February 8, 2024:

February 13 to integrate Biogen earnings readout

February 24 to integrate BioMarin earnings readout

February 29 to integrate Leqembi prescriber insights from Spherix

March 21 to integrate BioNTech earnings miss

May 9 to integrate Takeda’s $900 million restructuring

May 22 to integrate Pfizer’s new cost cutting program

July 24 to integrate the CDC’s restricted endorsement of RSV vaccines

July 26 to integrate the European Medicine Agency’s rejection of Leqembi

September 12 to integrate “the crash” at Moderna

October 7 to integrate activist Starboard Value taking $1 Billion stake in Pfizer

October 25 to integrate analysis by LEK that found half of all drugs launched in the past 15 years underperformed pre-launch forecasts by more than 20 percent

November 6 to integrate Stephane Bancel stepping down as chief commercial officer of Moderna

November 7 to integrate vaccine stocks dropping on worries over RFK Jr. role in Trump adminstration

November 8 to integrate Eisai lowering Leqembi revenue forecast after “rocky entry” to market

November 12 to integrate Novavax stock plunge after its 3Q earnings read out

February 6 to integrate Bristol Myers Squibb announcing another restructuring, plans to cut $2B in costs

February 10 to integrate public reaction to Pfizer’s new campaign launched at “The Big Game”

Listen to Hardcore Zen

Unique Genre Required

Lex is the flagship investment column of the Financial Times. Its commentaries, currently written by a team of eleven investment writers in five times zones, has been published daily in the newspaper since 1945. “We believe it is the most influential column of its kind in the world”, says the paper.

On Tuesday this week, the commentary was about market strategy in the pharmaceutical industry: ‘Big Pharma Still Needs Trial Success to Overcome Looming Patent Panic’.

“It is a tale as old as time. Pharmaceutical companies must replenish their drugs pipeline before exclusivity rights on top-selling products expire. But even though Big Pharma knows what the ending should be, the companies don’t always get the plot right.

Risks from patent expiries have been relatively low since 2020. But the percentage of prescription drug sales at patent risk industry-wide in 2027-2028 will reach the highest level since 2015, reckons Evaluate.

In theory, it should be slightly different this time — compared with the patent panics of the past. The move towards harder-to-copy biologic drugs means drugmakers do not face such a steep drop-off in sales after exclusivity expires. Companies have become more adept at protecting key drugs, both through litigation and by seeking approvals in new diseases…..

….This time, as in the past, only innovation and trial success will lead to greater conviction that this classic story has a happy ending.”

That there’s still “panic” at the patent cliff at all is mind-blowing, when you think about it. What happens at LOE should surprise no one. The problem is the plotline, the story itself, the “screenplay” commercial teams in the drug market are following in the hope for a happy ending.

To wit, via Barron’s coverage of BioNTech earnings readout on March 20:

“BioNTech stock tumbled to its lowest point in three years Wednesday after the Covid vaccine maker reported light fourth-quarter sales and profit, and delivered lackluster 2024 guidance. On a conference call, BioNTech execs said the company was "surprised" by the level of fourth-quarter inventory write-downs at its COVID-19 partner Pfizer.”

Moderna, who like Pfizer came to the world's rescue during the pandemic, yesterday slashed its research and development budget by more than a billion, cut its 2024 sales outlook for its vaccine franchise, and delayed its breakeven point by two years. Moderna's stock crashed more than 12 percent on the news, having tumbled from its all-time high above $449 in September 2021 — a wipeout of nearly $170 billion of market value over the three years.

The "bull thesis continues to weaken" for Moderna stock, Leerink Partners analyst Mani Foroohar said in a client note. "Its R&D reductions are too far out chronologically to be credible from a management team that we think has proven serially unable to project the performance of their business."

The only real surprise are management teams still being surprised.

Last week, Takeda reported that its annual profits for FY 2023 have been hit by more than 50 precent, prompting the company to say it will initiate “several plans to optimize its workforce and prioritize its pipeline” — after 16 years on the market, Takeda lost exclusivity for its attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medication Vyvanse in mid-2023. Sales totalled $2.7bn for FY 2023, with Takeda expecting a further drop of 47 percent in sales for FY 2024.

And like pretty much everyone else, Takeda said it will “pivot to data, digital and technology to increase productivity and efficiency across the organization”. In other words, nothing particularly novel or unique in the storyline.

Operations isn’t strategy. And all technology is operations. From What Strategy is Not published by Blue Spoon in Sloan Management Review:.

“Strategy is not technology. No one gains competitive advantage from letting technology lead strategic visioning. This is the short road to parity. The ever-expanding universe of specialized technology applications makes possible almost any conceivable operational vision, but strategy is not forged from technological (or economic) power alone. Strategic understanding cannot be keyed to a specific technology application. When the same communication and knowledge acquisition technologies are accessible to everyone, and everyone works with the same set of ideas to deploy technology in the same way, there is competitive convergence. Commoditized performance sets in because actors are copying one another using cut-and-paste methods. Advantage instead flows from getting ahead of the technology curve and using holistic thinking to guide the process of change. This is concept-driven innovation, a very different sort of framework than technology-driven innovation.”

The world works with rules that few in the West understand. And all the linear frameworks, market expectations and demand forecasting based on expert knowledge of the past -- the 'business case' we’re taught to follow and sell and use as the basis for forecasting -- doesn't work, not anymore.

Quoting Hunter S. Thompson: “We are living in dangerously weird times now. Smart people just shrug and admit they're dazed and confused. The only ones left with any confidence at all are the New Dumb. It is the beginning of the end of our world as we knew it. Doom is the operative ethic.”

The Flop Era Returns

Another day, another economic system finds itself scrambling to stop strategic collapse, searching for original solutions, but stuck rotating in an orbit of obsolete economic concepts, trying to solve its existential crisis with a legacy narrative, confusing the PowerPoint for strategy.

But the map, as they say, is not the territory.

The reality problem -- the 'ground truth' for all the US Army veterans -- is deeper, wider and more complex, an almost virus-like infection that's been reproducing itself in all the pathways for decades, self-generating the code for its own survival.

It's a 'linear-hope-followed-by-expontental-scramble' form of management, of which Pfizer (and GSK and Walgreens and 23andMe and Teladoc Health) is but the latest victim.

An entire corpus of thought in the West is bankrupt, education and experience that starts in kindergarten, works its way through high school, gets reinforced in college and then culminates with a selfie posted on LinkedIn, showcasing an Executive Leadership Certificate from completing a program taught by similarly collapsing Harvard Business School, or similarly collapsing McKinsey & Company, or similarly collapsing Google.

No one understands the machinery, including the people in charge.

The thing that's not working is the base layer. Or more precisely a fragmentary worldview, now trying to break the hold of a massive feedback loop sustaining The Standard Model. You can’t invent the automobile if you’re trying to “fix” the horseless carriage.

In May Pfizer launched a new multi-year program to reduce costs as it works to rebound from the strategic collapse of its Covid business. The announcement is in addition to another $4 billion cost-cutting effort, which Pfizer announced last year as demand for its Covid vaccine and oral drug Paxlovid evaporated almost overnight. Reported CNBC:

“Pfizer is trying to shore up investor sentiment after its shares fell nearly 50 precent in 2023, making it the worst-performing pharmaceutical stock last year. That share drop erased more than $100 billion in Pfizer’s market value. As demand for Covid products plummeted last year, Pfizer also disappointed Wall Street with the underwhelming launch of a new RSV shot, a twice-daily weight loss pill that fell short in clinical trials and an initial 2024 forecast that missed expectations.”

Pfizer had a market value of about $162 billion as of Friday (October 4). Its shares have been roughly cut in half from a record high notched in late 2021 after it delivered the world’s first Covid-19 vaccine. They are little changed so far this year, compared with a 21% rise in the S&P 500. In breaking news (October 7), the Wall Street Journal reports that activist investor Starboard Value has taken a roughly $1 billion stake in Pfizer and “wants the struggling drugmaker to make changes to turn its performance around.”

Starboard has approached two former Pfizer executives, Ian Read and Frank D’Amelio, to aid in its efforts, and they have expressed interest in helping, the people familiar with the matter said. Read was Pfizer’s chief executive officer from 2010 to 2018 and handpicked current CEO Albert Bourla as his successor. D’Amelio was its chief financial officer from 2007 to 2021.

Pfizer’s Bourla has been under pressure from investors to right the ship at the drugmaker, especially after it overestimated future demand for pandemic-related products once the health emergency subsided.

“It is not overly surprising to see a firm such as Starboard make an attempt to change the trajectory of the company,” Mizuho health-care specialist Jared Holz said in a note Sunday night. “The entire concept of PFE’s aggressive business development strategy and lack of return (so far) is likely one of the major reasons behind the Starboard stake.”

Welcome to the era of bleak prognosticating, where the only surprise is management teams still being surprised.

Two Headlines, Six Months Apart

On Sunday (October 6), we get an update from The Analysts:

This season’s uptake of RSV vaccines in the US has been slower than expected, and appears to be missing even modest projections for growth compared with 2023.

Last year at this time, per reporting by Endpoints News, 1.5 million prescriptions had been issued for the vaccines. But this year, only 900,000 have, according to Jefferies. That represents a 40% drop compared to last year.

In related/unrelated news, via the Wall Street Journal: Vaccine Stocks Drop on Worries About an RFK Jr. Role

“Stocks of vaccine-makers were underperforming on Wednesday, with Pfizer and Moderna both down around 2% while BioNTech was trading 2.5% lower.

Donald Trump said on Tuesday that Kennedy, an anti-vaccine activist, could “do pretty much what he wants” in his administration. The comments didn’t clarify what specific role Kennedy would play. In a video posted last week, Kennedy said that Trump had “promised” him control of several health-focused governmental offices, including Health and Human Services.

The reaction could very likely be premature given that Trump might wind up not giving Kennedy a position, and Senate confirmation for such a controversial figure would be an uphill battle. “Shoot first reaction being felt across the vaccine complex,” wrote Jared Holz, a healthcare strategist at Mizuho, adding that “for now, state mandates for many treatments remain intact.”

There is plenty of populist anger on the right with vaccine-makers and agencies like the Food and Drug Administration. Whether that gets translated into real policy or a Cabinet post is something some investors don’t want to stick around to find out.”

Moderna has lost about 43 billion in market value in the last five months and Stephane Bancel is stepping down as chief commercial officer. And on Novavax's 3Q earnings call, which was followed by a “stock plunge” of more than 6% after the company lowered its guidance for sales for the year and announced it was cutting R&D by $1.4 billion versus 2022, Novavax chief executive John Jacobs said the company needs to recover from its struggles to commercialize the COVID vaccine and get the company into profitable territory. "We're going back to our roots. It's hitting the reset button and now starting to pivot our way. This is our last season fighting this fight," he said in an interview. "We were hopeful to get a larger market share this year,"

Hope isn’t a strategy.

Here’s some content Blue Spoon uses in broad-framing workshops with pharmaceutical brand teams..

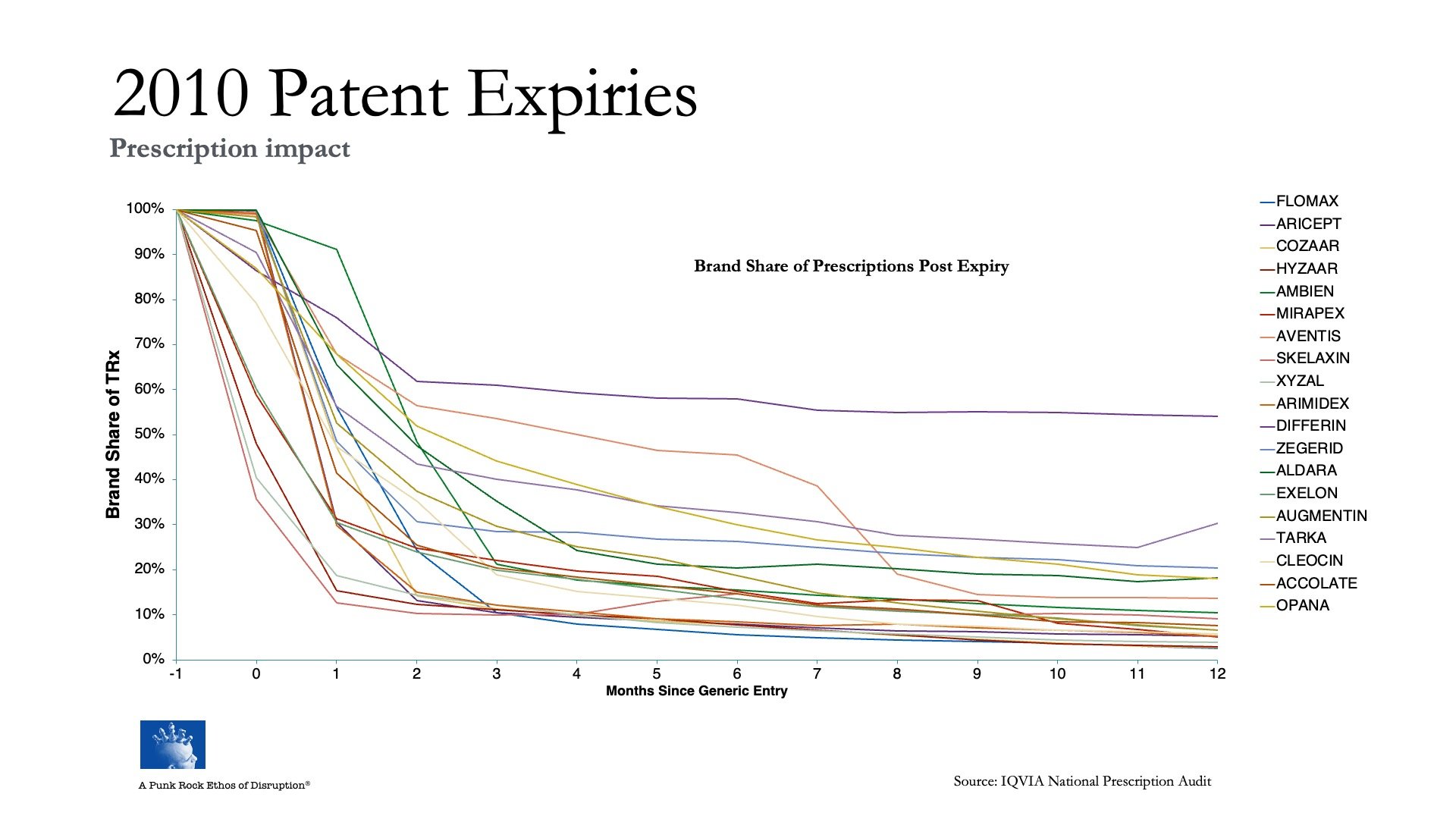

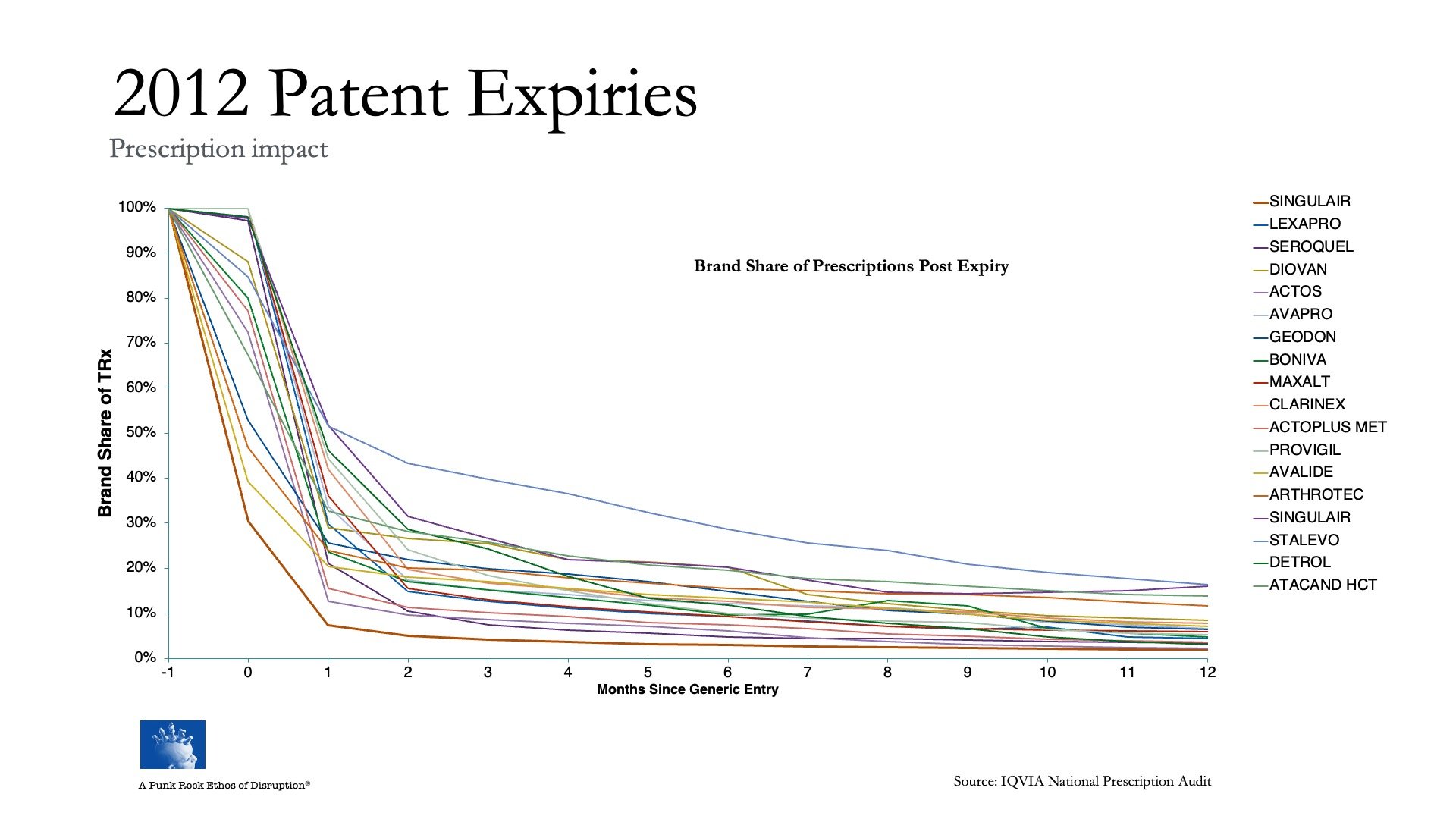

This looks at the success rate (failure, really) of strategies to stop, or at least divert, the drug patent bus before it runs off the cliff for about 40 different drug brands, collectively generating hundreds of billions in revenue, at a period when the industry as a whole was facing another big cycle of patent expirations:

Not one brand was able to stop itself from going over the cliff. Not one.

You could ask, Is 2010-2012 data still relevant today?

Think about it this way:

Each of these 40 drug brands was managed by brand teams of hundreds, if not thousands of very smart people with deep knowledge of their markets, who in turn relied on tens of thousands of equally knowledge people working across an entire economic system — marketing services vendors (agencies like WPP, Omnicom and Interpublic Goup, all also searching for commercial model innovation in the face of AI-driven dislocation), as well as the ‘thinking partners’ used by executive leadership teams and boards (strategy advisors like McKinsey and Boston Consulting Group, dealing with the same commercial-model innovation problems as the agencies) — to guide them, support them, and come up with “creative” ideas to help them grow their businesses.

Or you could just look at the analysis published by LEK earlier this year:

Failure to Launch as Expected

About half the drugs launched in the last 15 years underperformed analysts’ sales estimates by more than 20%, according to a recent report from L.E.K. Consulting. In fact, only one-fifth of new meds reached $1 billion in U.S. sales, and more than half failed to hit even $250 million.

All the data suggests this: everyone is struggling with model collapse. Everyone.

An entire system of thought is stuck, trying to squeeze more juice out of a cognitive pattern that hasn’t changed since the Industrial Age. In other words, the elephant in the room is the room itself, an approach to business and product marketing unchanged sine the “modern pharmaceutical industry” began around 1849, when Pfizer was founded in Brooklyn.

And for evidence of this, look no further than Amgen “doubling down” on the Standard Model: a DTC campaign on the dangers of high cholesterol (Amgen markets and sells Repatha, a PCSK9 inhibitor that reduces LDL cholesterol — it was approved in December 2017. Amgen faced initial backlash over its $14,000 per year price tag, and cut the price by 60% the next year. Its current list price is $6,738 per year.) Or touting safety risks of generics as part of a strategy to prevent switching — Bayer did this with aspirin in one of the first DTC advertising campaigns….in 1917.

So the question for pharmaceutical brand teams is this: are you really planning for a $250 billion in revenue loss from the patent cliff in 2028 with concepts from the turn of the 19th century, when “horseless carriage” was used to describe the first automobiles?

Time to Rewrite the “Classic Story” in Pharma

The Classic Story in pharma revolves around basic narrative plots, frameworks that are recycled again and again in the drug market, regardless of the brand telling them.

These stories may be populated by different settings, characters, and conflicts, but the dominant themes are the big miss (i.e., completely misreading the demand environment); promotional tonnage (i.e., the push model); the quest (i.e., squeeze the push model even harder); death by a thousand reorgs (i.e., rearrange the deck chairs); and ultimately panic at the disco (i.e., the patent cliff and, now, having to negotiate price with the United States government as part of the Inflation Reduction Act).

The rough rollout for Eisai’s new Alzheimer's drug Leqembi is, I would suggest, what happens sticking with a ‘drug promotion’ script first written around the time the Model T was rolling off the assembly line. From EndPoints coverage of Eisai’s earnings call yesterday (With subpar sales for Leqembi, Eisai delays Alzheimer’s patient goal deadline):

“Eisai said it could struggle to meet uptake targets for its Biogen-partnered Alzheimer’s drug Leqembi by the end of March as it detailed disappointing fiscal third quarter sales for the intravenous therapy.

Leqembi won US accelerated approval in January 2023 with full approval following in July. Eisai has high hopes for the treatment, projecting it could reach $7 billion in global sales by 2030.

But Leqembi sales of almost $7 million in the three months leading up to December 2023 fell short of Visible Alpha consensus estimates of $9.3 million. The drug has been administered to around 2,000 patients in the US, with four times that number on wait lists, Eisai’s global Alzheimer’s officer Keisuke Naito said on its earnings call Tuesday. Eisai anticipates a one to three month delay to reach the 10,000-patient goal, but Jefferies analysts said it could take longer seeing as “launch dynamics have been slow to begin with.” The Japanese pharma spent roughly $505 million to promote Leqembi in the fiscal year to date.

Eisai is focused on supporting US medics to establish early Alzheimer’s diagnosis and treatment pathways covering “treatment policies, SOPs and other processes that differ from one medical institution to another,” per a company presentation."

You don't need to read the company’s PowerPoint to predict where this is going.

And in the United States:

Biogen fell the most in two years as its latest foray into Alzheimer’s disease got off to a slow start, suggesting a long road to growth for the biotechnology giant, reported Bloomberg in its coverage of the company’s earnings read-out on February 13 (see Biogen Plunges as Alzheimer Drug’s Slow Uptake Signals Reset). “There’s plenty of demand from patients for the drug," Biogen CEO Chris Viehbacher told analysts on the call. “It really is a question of the system being able to accommodate this new flow of patients.”

Which speaks to the thing that is missing from the forecasts, the Big Misread: it’s the strategy at a system level that now determines commercial success or failure.

Neurologists Paint Bleak Leqembi Launch Picture as Alzheimer's Drug Trips Up on a Host of Challenges

FiercePharma, February 27 — It wasn’t supposed to be like this: Eisai and Biogen’s new Alzheimer’s disease drug Leqembi was supposed to be the chosen one after the flop that was Biogen and Eisai’s Aduhelm, but neurologists are voicing “frustration” at core elements of the therapy’s rollout.

That’s according to a stark new report out by life sciences consultants at Spherix that delved down into insights from 75 high-prescribing U.S. neurologists that work with Alzheimer’s patients.

The picture painted by them is bleak: Now around six months after the launch of Leqembi, “few surveyed neurologists consider Leqembi to be a significant medical advance over other historical AD treatments,” Spherix’s analysis found. It also found that satisfaction with Leqembi “is relatively low,” with the average satisfaction rating being a full 15% lower than the typical rating for a new neurology market entrant.

“Perhaps related to that, less than half of neurologists surveyed are actively recommending Leqembi to patients,” the report found.

Scientific achievement — technical potential of a drug — is no guarantee of financial success in the pharmaceutical industry. If anything, it’s almost incidental, table stakes in an operating environment that is marked by mushrooming complexity and fragmentation. It’s a painful, and expensive, lesson in commercial model innovation that often comes too late for many product marketing teams at drug manufacturers, including the vendors advising them on product marketing.

To wit gene therapy pioneer BioMarin, which has only one patient (emphasis added) on its “miracle cure” — via Bloomberg’s Gerry Smith.

BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc.’s new treatment for an inherited bleeding disorder was supposed to be a triumph. Aimed at a larger group of patients than the biotech company usually targets, Roctavian was its first foray into gene therapy, a promising field of medicine that fixes genetic flaws to potentially cure diseases.

So far, Roctavian has failed to gain traction in treatment of hemophilia A—just one paying patient in the US was treated with the therapy from the time it won approval last June through the end of 2023, Chief Executive Officer Alexander Hardy said in January at the JPMorgan Healthcare Conference. For a product that was once expected to deliver more than $100 million in 2023 revenue, it’s a grave disappointment.

When Reservoir Dogs hit theaters, it rocketed Quentin Tarantino from obscurity into one of the most influential directors in film history. His groundbreaking tale of crime and betrayal reinvented independent film. Tarantino's approach is to focus on characters, not actors. In an interview with SPIN (Quentin Tarantino: Our 1992 Interview):

Commenting on his wrecking crew, Tarantino notes: “You have a collection of acting styles. You have Harvey, who is Method; Steve Buscemi, who comes from an underground theater background; Michael Madsen — a very naturalistic, unaffected, un-actor-y sort of actor. Lawrence Tierney has his Lawrence Tierney thing. You have all these personalities working together and that’s what creates the tension — and creates the fun about it.”

"It’s all about my characters. I actually think my characters are going to be one of my biggest legacies after I’m gone. So I have no obligation whatsoever other than to just cast it right."

Regardless the industry, and the economic subsystem of vendors and advisors an industry uses to create and innovate and figure out where to go for growth, 'commercial model innovation' ultimately comes down to telling and selling a new strategy story. It is cast with unique characters in different combinations and collaborations that create space for tension and fresh dialogue.

It’s something that looks and feels more like Quentin Tarantino than old-school Hollywood (on that score: “With ‘Megalopolis,’ the Flop Era Returns to Cinemas — Plenty of movies bomb, but Francis Ford Coppola’s latest is part of a different class of box office failures” via the New York Times on October 5).

"China is one of the fastest-aging countries in the world and is one of the most important countries in the area of Alzheimer’s disease for Eisai,” the company told Reuters yesterday. “The potential growth for Leqembi in China is huge.”

When all else fails, ride the demographic dividend: many people = many people with an existing or emerging health problem = huge market opportunity.

Which is another classic story for Western companies seeking growth in China. And for the pharmaceutical industry, the value equation is almost a no-brainer to package and position in one slide for investors. But the reality is more complex, and certainly not linear (see here China’s “demographic dividend” appears to be a myth). And as pharmaceutical commercial teams are realizing, competing in China means giving “mega-discounts” to get market access. From Bloomberg (How China Is Getting Drug Companies to Slash Prices):

“China has been overhauling its health-care system with the aim of providing broader access to quality drugs for its enormous population. The result: Drug prices are tumbling and the once-high profit margins of drugmakers, both local and foreign, are eroding. For manufacturers, the pressure is set to intensify as China hones its strategy of demanding mega-discounts in exchange for access to the world’s No. 2 pharmaceuticals market.”

Huge growth opportunity for Eisai and its Alzheimer’s drug in China? Or Biogen in the United States? We'll see.

When it comes to commercial model innovation in the drug market, you can either hope for the best from "the system" already out there somewhere, or you can simply chop the knot and construct your own channel, become the visible hand and construct a new system of markets, where the markets themselves become characters in a new screenplay. Something unique and original. Something that, like Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs, delivers an ‘innovation shock’ to the audience.

More to the hundred-billion-dolllar point:

If the Leqembi brand teams at Biogen and Eisai stick with the Classic Story, following the same script, using the same cast of character that has framed the industry’s narrative for the past 175 years, my over/under betting for a “happy ending” is with the under. To wit: On November 8, Eisai lowered Leqembi revenue forecast after “rocky entry” to market, per Pharmaceutical Technology.

“In a statement to Pharmaceutical Technology, a company spokesperson said “[The] momentum continues to build for Leqembi week over week and we recognize the great potential for market expansion ahead”.

Whilst not mentioning regulatory updates in the UK, Eisai’s forecast revision comes just a few months after Leqembi was deemed too expensive for use by the National Health Service (NHS). Though licensed for use in the country, England’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) said at the time the benefits of the treatment were too small to justify its cost. Eli Lilly met the same fate with its Leqembi rival Kisunla (donanemab), which was also rejected for NHS use last month. In another setback, Leqembi failed to win over the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in July this year after a committee recommended against the therapy’s approval.

EU sales were expected to contribute as much as $1.6 billion in peak sales for Leqembi. Shares in Biogen were down almost 6 percent on Friday following the news. And in a related story that should surprise no one, GSK, Pfizer and Moderna “could see almost a threefold drop in demand” for their vaccines for RSV after the CDC narrowed its recommendations, wrote the Financial Times last week. “The US market for RSV in elderly adults could shrink from $4.7 billion a year by 2030 to $1.7 billion.”

In July when GsK shared the quarterly results above, CEO Emma Walmsley said that “with a best-in-class data profile, we are confident Arexvy will return to growth next year and longer term can achieve more than £3 billion in peak year sales.”

I wouldn’t bet on it.

/ jgs

John G. Singer is Executive Director of Blue Spoon, the global leader in positioning strategy at a system level. To engage with a mind stretch: john@bluespoonconsulting.com