A Merck-Verizon Acquisition?

The 'Crazy Hypothetical' as Spark for Strategic Imagination

When it happens, America’s stock market crash will be one of the most predicted financial implosions in history. The blast radius — the zone of second- and third-order consequences created from the collapse of a dominant node or narrative — will be global and personal. The terrain affected will become some sort of a three-dimensional rubble.

The Economist, writing last week in How Markets Could Topple the Global Economy:

“It would be a mistake to think that the effect of big stock market losses would stop at the wallets of investors, The longer the boom goes on, the more opaque its financing becomes. And even without financial Armageddon, a dramatic stock market fall might at last topple a hitherto resilient world economy into a downturn.

The root of the vulnerability is the American consumer.

Stocks account for 21% of the country’s household wealth —about a quarter as much again as at the height of the dotcom boom. Assets related to AI are responsible for nearly half the increase in Americans’ wealth over the past year. As households have become wealthier, they have grown comfortable saving less than they did before the Covid-19 pandemic.

A crash would put these trends into reverse.

The shock, and weaker American demand, would spill over to low-growth Europe and deflationary China, compounding the blow to exporters from President Donald Trump’s tariffs. And because foreigners have $18trn-worth of exposure to American stocks, there would be a mini-wealth effect globally.”

The numbers have become so large, and the largeness repeated so often, that the scale and speed and spread no longer registers on the collective capitalist consciousness, to say nothing of the personal one. When you live in The Spectacular Now, it can be hard to find ‘narrative surprise’ from which to spark behavior change, to persuade, to break the hold and the mold of a noisy stasis.

Big tech companies are expected to spend nearly $3 trillion on AI through 2028 but only generate enough cash to cover half that tab, according to analysts at Morgan Stanley. Executive leadership of the financial world, including Goldman Sachs CEO David Solomon, are warning about AI-fueled froth from all the FOMO. Speaking in October at Italian Tech Week in Turin, Italy, Solomon said a “drawdown” was likely to hit stock markets in the coming two years, and that we should all be “skeptical” of the math. “I think that there will be a lot of capital that’s deployed that will turn out to not deliver returns,” he said.

[Days after Solomon voiced his concerns, Goldman formed a new team focused on selling AI infrastructure financing, to “build the AI factories of tomorrow by rewiring how capital flows into the AI ecosystem.”]

Borrowing from Full Metal Jacket, Stanley Kubrick’s take on the Vietnam War based on Gustav Hasford’s book The Short-Timers:.

“In strategic terms, [the Big Tech vision] has cut the country in half... the civilian press are about to wet their pants and we’ve heard even Cronkite’s going to say the war is now unwinnable. In other words, it’s a huge shit sandwich, and we’re all gonna have to take a bite.”

Including 15,000 middle managers at Verizon, who will be losing their jobs this week as part of the company’s largest ever layoffs. Verizon — like WPP and Starbucks and Walgreens and Moderna and Nestlé — flailed for years to ‘jump out’ of the feedback loops powering strategic decay and, ultimately, collapse. Verizon chairman Mark Bertolini said on CNBC last week that the company’s new CEO, former PayPal chief executive Dan Schulman, is working to revive Verizon from its period of share losses under former CEO Hans Vestberg.

Bertolini, who is also the Oscar Health CEO and who was named Verizon chairman last month, told CNBC’s Becky Quick on “Squawk Box” that the company needs to “do something different” as it undergoes its leadership change.

“Verizon has gone from number one in market cap, bond ratings and market share to number three. And the network isn’t as differentiated as it used to be, in large part because everybody’s been spending money to put these 5G networks in place,” Bertolini said. “So losing 30% share over the last eight years is an issue, and we have to do something different.”

Which is what WPP and Starbucks and Walgreens and Moderna and Nestlé all said.

In reality, of course, strategic collapse is often a matter of grim erosion, taking place over years and repeated bloody incidents. As Shakespeare well knew, we don’t usually become who we are in one defining moment. Much of it is genetic. Much of it is based on flawed beliefs about how the world works.

A ‘Crazy Hypothetical’

The Wall Street Journal this morning published a deep piece of journalism that, in its broader framing of how “Wall Street Blows Past Bubble Worries to Supercharge AI Spending Frenzy”, touches on deal-making in the Spectacular Now, where literally nothing is off the table when you play in the zone of computational imagination. An extended excerpt:

About a year and a half ago, bankers at JPMorgan got a call from a longtime client with what sounded like a crazy hypothetical: How would you finance a project to build a campus of AI data centers that would draw one gigawatt of power?

The bankers told their client, a developer and landlord called Vantage Data Centers, that it would never need that much capacity. But they walked through how they would theoretically raise the money.

Earlier this year, Vantage called JPMorgan to say it wanted to pull the trigger, with one tweak. Instead of building a single 1-gigawatt data center, it wanted to build two of them. Not long after, JPMorgan and a group of other banks agreed to lend $38 billion for a data center in Texas’ Shackelford County and another one outside Milwaukee, Wis.

The five-year debt package, named Jacquard, was so jumbo-size that more than 30 other banks, from global giants such as JPMorgan to regional players such as U.S. Bancorp, were tapped to sell portions to investors. They are [now] pitching insurers, corporate debt funds and almost every type of bond buyer.

“What we do know for certain is that the [big tech companies] that want the world to spend trillions have huge financial incentives to be believers. In case you haven’t noticed, Wall Street is also being paid a lot to promote the story,” Greenlight Capital, the hedge-fund firm run by David Einhorn, wrote in an October letter to investors.

The problem with the story being promoted — the narrative contagion that seems tuned to a particular pattern of morbidity based on economic churn — is that it’s missing its lead actor, the protagonist in Sam’s screenplay: the production of data. Humanity is being emptied. We’ve run out of enormous new and novel datasets to power the compute. Says EpochAI: a key question in forecasting AI progress is whether inputs other than raw compute could become binding constraints. Their conclusion? “Our 80% confidence interval is that the data stock will be fully utilized at some point between 2026 and 2032. (To dig deeper on this ‘missing loop’, see Can Big Pharma Save Big Tech From Strategic Collapse? published by Blue Spoon.)

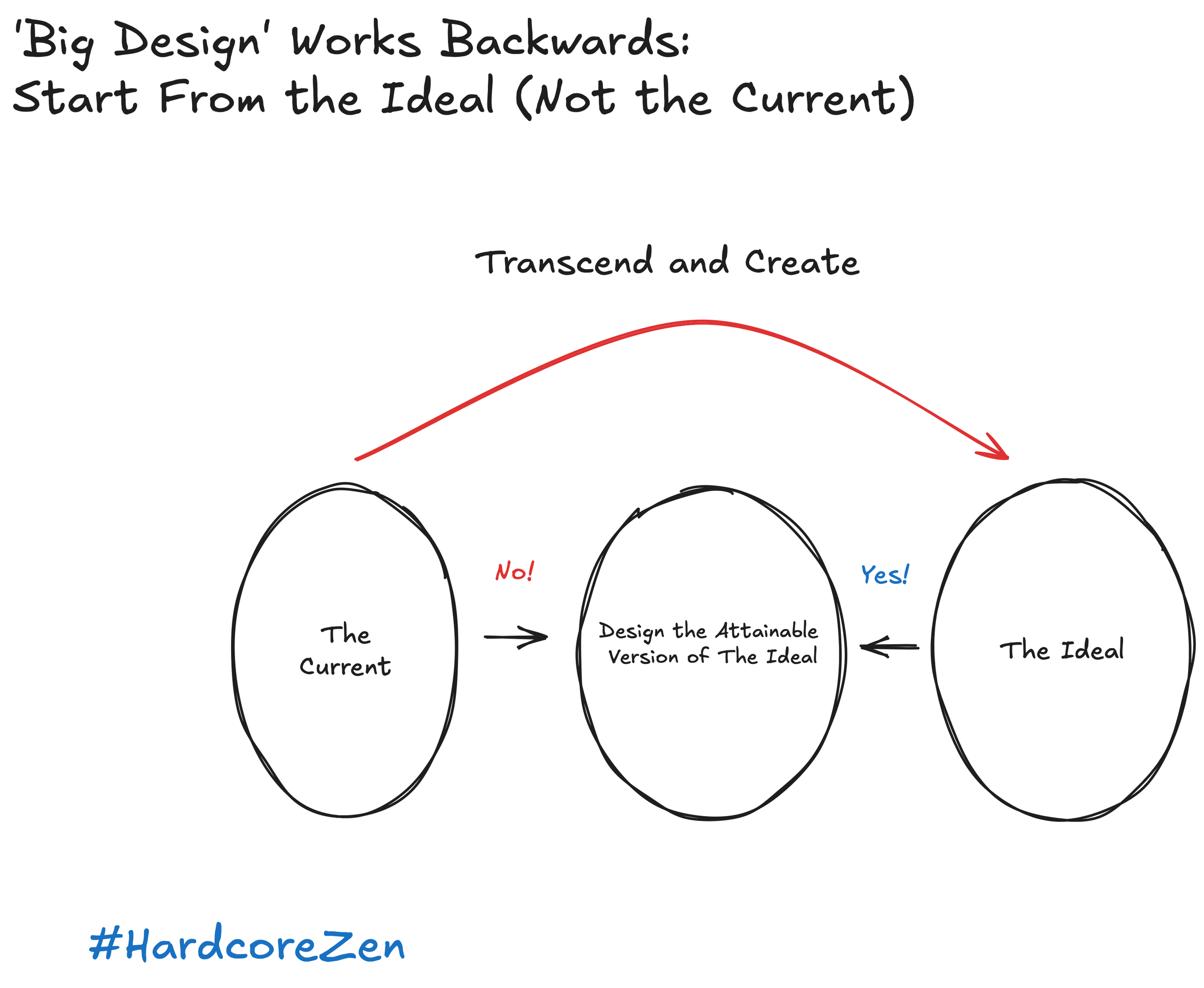

Start Bigger, Works Backwards

Project Hieroglyph was founded by Neal Stephenson and produced by Arizona State University’s Center for Science and the Imagination. The center is about the strategic imagination and bigger innovation that happens from ‘differential connectedness’ — bringing writers, artists and other creative thinkers into collaboration with scientists, engineers and technologists to “reignite humanity’s grand ambitions for innovation and discovery.”

The center serves as a network hub for audacious ideas and a cultural engine for thoughtful optimism.

A Merck-Verizon acquisition is not feasible in any realistic strategic, regulatory or economic sense. The market caps make it almost impossible, and there’s no strategic rationale large enough that could be packaged and sold as a board-level rationale. Telecom is considered a strategic national infrastructure of the United States, almost like energy or defense. Regulators would block it before negotiations even started. Capital markets would reject it immediately.

But what if you start with a different technique to see and think and do big stuff?

Audacious projects like the Great Pyramids, the Hoover Dam, a moon landing (or building data centers in space), didn’t just happen by accident. Someone had to imagine them and create a narrative that brought (sold) that vision to life for others, that inspired others to get out there and make them real.

So in that spirit, working the space of the ideal and the counterfactual, if Merck did acquire Verizon, what would the strategic logic be? In a fictional-but-plausible world, the only viable rationale would start by Merck reframing Verizon, casting it differently in the screenplay. It’s role is not as a telecom, but as a ‘strategic national health data utility’ (almost like the VHA or NHS), the physical layer controlling data flow, an API layer for population-scale telemetry enabling real-time monitoring, the equivalent of buying the railroad and pipelines needed to industrialize the next century or personalized medicine and economics.

This is a future where ‘continuous health engagement’ is as economically essential as electricity. Where ‘drug value’ is measured through data loops and specialized cognition, not drug manufacturing, and where employers-as-payers demand real-world, real-time evidence for pricing and negotiating based on the transparent production of affordable health. Merck essentially becomes the Foundry of Continuous Health Engagement that runs on Verizon’s network.

Merck argues it can unlock $100B+ in new value pools by collapsing drug development, remote monitoring, real-world evidence, at-home clinical trials and adherence infrastructure. Verizon’s stagnating assets become growth assets through healthcare monetization. And to get regulators on board, Merck positions the narrative as a merger at the level of statecraft, not commerce. (To dig deeper on this, see Pfizer Plays Geoeconomics published by Blue Spoon.)

Drugs become interfaces into a data loop. Networks become the arteries of a portfolio of new economic systems (there’s not just one “AI ecosystem” out there, but thousands of them). And pharma becomes a new control point, casting AI not in the leading role, but as part of the crowd scene; it becomes the interpreter of continuous diagnostics and continuous health engagement, a tool to enable the production of health data and self-generating markets, at infinite scale.

The Art of the Frontier Narrative

It becomes almost a matter of code breaking, of breaking the work down into a structure that is truthful, that doesn’t lose the ideas or the content or the feeling of the book, said Kubrick in an interview with Rolling Stone after the release of Full Metal Jacket.

As long as you possibly can, you retain your emotional attitude, whatever it was that made you fall in love [with the story] in the first place. You judge a scene by asking yourself, “Am I still responding to what’s there?” The process is both analytical and emotional. You’re trying to balance calculating analysis against feeling.

And it’s almost never a question of “What does this scene mean?” It’s “Is this truthful, or does something about it feel false?” It’s “Is this scene interesting? Will it make me feel the way I felt when I first fell in love with the material?” It’s an intuitive process, the way I imagine writing music is intuitive. It’s not a matter of structuring an argument.”

The question becomes, are you giving them something to make them a little happier, or are you putting in something that is inherently true to the material? Are people behaving the way we all really behave, or are they behaving the way we would like them to behave? I mean, the world is not as it’s presented in Frank Capra films. People love those films — which are beautifully made — but I wouldn’t describe them as a true picture of life.

Sam’s vision feels false to me because it doesn’t make sense strategically. It’s not a true picture of life.

Underneath that facade of computational perfection is exactly the mess of interconnected systems, policy frameworks, people, assumptions, infrastructures, and interfaces that operate in the gap between code and culture, with the duality of man. It’s in this “unfixable” space where new industry + human narratives will be born, with the Radical Solution.

It’s a hardball world, son. We’ve just got to keep our heads until this AI craze blows over.

/ jgs

John G. Singer is Executive Director of Blue Spoon, the global leader in positioning strategy at a system level. Blue Spoon specializes in conturing new industry narratives.