What Hath Sam Wrought?

The AI Economy Needs Humanity to Save IT From Itself

Trillions will be spent (invested?) this decade to build AI infrastructure, numbers so unimaginably large that they defy the bounds of modern mathematics and normal (is anything “normal” anymore?) strategic logic.

“We do see some signs of irrationality,” says Antonio (Tony) DeSpirito, global chief investment officer at BlackRock Fundamental Equities.

Some?.

For a reference point: The Apollo program allocated about $300 billion in inflation-adjusted dollars to get the United States to the moon between the early 1960s and the early 1970s. The Great AI Buildout now in the throes of its own feedback loop requires companies (and the government, which is to say taxpayers) to collectively fund a new Apollo program, not every 10 years, but every 10 months.

It’s a big ambition that may hold for a certain kind of thinker, or more specifically, a system of thinkers who base their beliefs and align themselves around a similar cognitive operation. The flimsiness of these gambits is part of their appeal: we’re being invited to play along, and if we don’t, we risk coming across as scolds or even worse, a Luddite. Wouldn’t it just be so much more pleasing and psychological comfortable to simply buy into the promise, that the humanity-saving claims are at least plausible?

Sam Altman’s dealmaking blitz “has convinced Silicon Valley’s giants to tether their fates to his company, essentially making it too big to fail,” writes Berber Jin in How Sam Altman Tied Tech’s Biggest Players to OpenAI, his piece of investigative journalism for the Wall Street Journal published this morning.

For almost a decade, the Nvidia chief executive had supplied the AI chips that powered OpenAI’s rise. Huang wanted to be the one unveiling such a giant deal with OpenAI’s CEO, according to people familiar with his thinking.

Soon after, Nvidia secretly pitched OpenAI on a similar project, offering to effectively sideline SoftBank and help raise the funds needed to build new data centers itself. The talks culminated in a giant $100-billion deal between the two companies, announced at Nvidia’s Santa Clara headquarters last month.

“This is the largest computing project in history,” Huang said.

Altman might not have intended to give Huang FOMO, or the fear of missing out, but he had that effect. And it is getting contagious.

To achieve his vision of securing seemingly endless computing power for OpenAI, Altman has gone on a dealmaking blitz, playing the egos of Silicon Valley’s giants off one another as they race to cash in on OpenAI’s future growth.

The resulting game of financial one-upmanship has tied the fates of the world’s biggest semiconductor and cloud companies — and vast swaths of the U.S. economy — to OpenAI, essentially making it too big to fail. All of them are now betting on the success of a startup that is nowhere near turning a profit and facing a mounting list of business challenges.

Altman’s success so far may well tell us something about how faith functions in the Valley, the trope of manifest destiny that reminds you of a tent revival: the mantra-like phrases, the messianic gurus, the cult of genius that barely manages to cover up its religious dimensions.

“The most successful people I know believe in themselves almost to the point of delusion,” Altman once wrote in a 2019 blog post titled “How To Be Successful,” before adding: “Self-belief alone is not sufficient — you also have to be able to convince other people of what you believe.”

There is a historic chasm between capex spending on AI and AI revenue.

Annual AI-related data-center spending in 2025 is around $400 billion, while AI revenue this year will total about $60 billion. “That’s a 6x-7x gap,” explains Derek Thompson in a recent Substack. “By comparison, the capex-revenue ratio for telecom companies during the dot-com fiber-optic bubble was about 4x; for the railroad companies building the transcontinentals in the 1870s, it was 2x. It is never a good sign to find a statistic that says today’s tech boom is three times more “bubbly” than the 1870s railroad build-out (which crashed and burned constantly) and 50 percent frothier than the dot-com bust.”

A Self-Licking Ice Cream Cone

Ever since the viral launch of ChatGPT, Altman has pumped up AI’s world-changing potential more than any other tech CEO, writes Jin, “prophesying a world where the technology finds a cure to cancer, provides customized tutoring to every student on earth, and becomes an endless gusher of profits for the companies behind it.” [Note to Sam: Researchers at Harvard and Stanford found that many firms are misusing AI so badly that workers spend more time fixing AI-generated “workslop” than doing their jobs.]

He wants OpenAI to be at the center of this transformation, and recently told employees that the company’s long-term goal was to build 250 gigawatts worth of computing capacity by 2033 in order to make it happen. Such a plan would cost more than $10 trillion by today’s standards and be enough to power a mid-sized country like Germany.

“The AI companies are all in bed with one another in a way that I do not explicitly intend as a description of San Francisco nightlife,” Thompson says. “Anthropic uses Amazon’s web services to power its models, and Amazon is also an investor in Anthropic. Microsoft invested in OpenAI and books cloud revenue from OpenAI. Nvidia and Advanced Micro Devices buy equity in companies to which they sell chips.” It’s a byzantine level of corporate entanglement and economic complexity impossible to decipher or untangle (it’s a “financial ouroboros” much like the US healthcare system).

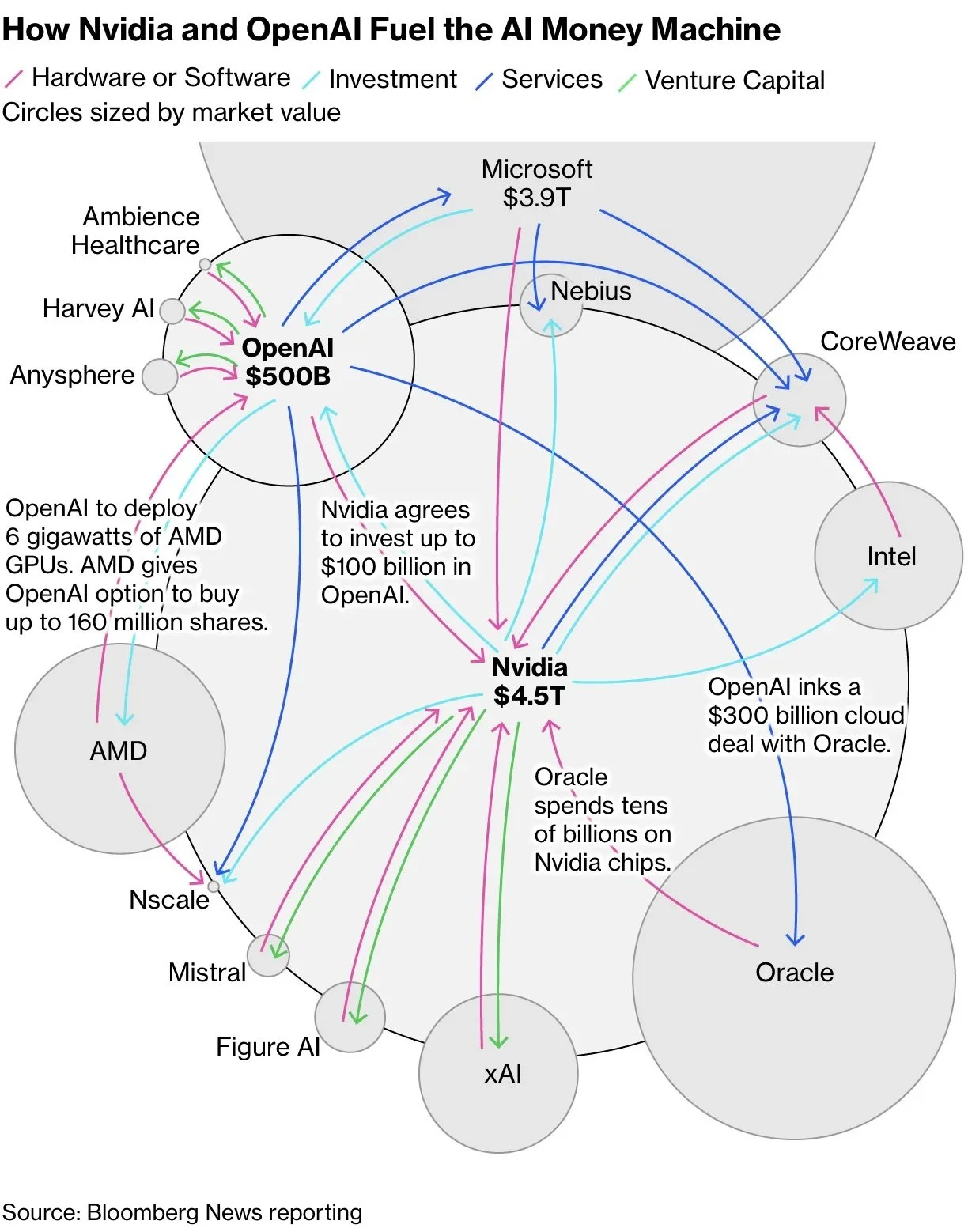

Bloomberg made this illegible situation moderately more legible with this infographic of AI’s weird corporate polyamory:

“I have learned over my career, again and again and again, you just have to trust the exponential,” Altman wrote in his blog post on success. “We’re not built to conceptualize it, but you just have to trust.”

From Tailwinds to Headwinds

Even if AI keeps advancing, major productivity gains may take decades because economic systems (ecosystems) must self-organize around new capabilities and new ‘concepts of operation’ — think moving from “horseless carriage” to ‘automobile’ (to conceptualize this, see Pharma’s Magic Quadrant: A Whiteboard to Help Get Out of Your Main Character Syndrome). But that offers little relief for today’s struggling economies and struggling middle class.

Michael Beckley in a piece for next month’s Foreign Affairs (The Stagnant Order):

Global growth has slowed from four percent in the first decades of the twenty-first century to about three percent today — and to barely one percent in advanced economies. Productivity growth, which ran at three to four percent annually in the 1950s and 1960s, has fallen close to zero. Meanwhile, global debt has swollen from 200 percent of GDP 15 years ago to 250 percent today, topping 300 percent in some advanced economies.

The demographic outlook is equally bleak. Today, nearly two-thirds of humanity lives in countries with birthrates below replacement levels. Most industrialized nations are literally dying powers, shrinking by hundreds of thousands each year—some by millions—and emerging markets are not far behind. Only sub-Saharan Africa still has high fertility, and rates are declining even there. Recent estimates suggest that the global population will begin falling in the 2050s.

The implications for national power are stark.

As labor forces contract and retiree ranks swell, growth in major economies is projected to decline by at least 15 percent over the next quarter century, and for some, the hit will be several times worse. Making up that loss would require productivity gains of two to five percent a year — the breakneck pace of the 1950s — or longer workweeks, neither of which is realistic amid slowing innovation and mass retirement. Demographic decline also rules out any phoenix-like recovery. In the industrial era, even countries shattered by war could roar back: Germany after World War I, the Soviet Union and Japan after World War II, and China after its “century of humiliation” all returned bigger and stronger within a generation.

Today, as populations shrink, lost power may be gone for good.

The Industrial Revolution broke scarcity’s grip and made productivity the foundation of economic power and competition, vaulting societies from medieval to modern in under a century. A Briton born in 1830 entered a world of candles, horse carts, and wooden ships; by old age, that same person could ride a railroad, send a telegraph, and walk streets lined with electric lights, factory goods, and indoor plumbing. In one lifetime, per capita energy use multiplied five- to tenfold.

Today’s technologies, remarkable though they are, have not remade life as the Industrial Revolution did. An American apartment from the 1940s, with a refrigerator, gas stove, electric lights, and telephone, would feel familiar today. By contrast, an 1870s home, with an outhouse, water well, and fireplace for cooking and heat, would seem prehistoric. The leap from 1870 to 1940 was transformative; the steps since, far less so.

Power From The People

Uber launched its new “digital tasks” program in the US last week.

This new approach shows how the next version of the gig economy Uber invented is forming in real time. Drivers can now earn by tagging photos, recording voice clips, or verifying bits of data that train Uber’s AI systems. The same people who once drove passengers are now training the software that will one day drive itself.

Uber says this program gives drivers new ways to earn between rides. The market behind it is growing fast. Data labeling, the process of feeding AI models with human-tagged examples, is already worth about $5B and could reach $17B by 2030. Uber’s pilot in India and Latin America is now expanding to the US. The company has built its AI task system on the same app that millions of drivers already use, giving it an instant workforce.

People matter. They’re the pesky, complex human dimension factor that Big Tech visionaries like Altman seem to assume away, or hope can be automated away, by the “God-like powers of artificial general intelligence”. Claiming absolute omniscience is intoxicating and creepy at the same time.

Altman’s idea of a ‘gentle singularity’ is, I suppose, a way to soften the stance. And hey, if we need more infrastructure to enable compute, then building a hypothetical megastructure data center that orbits around the sun makes perfect sense as far as messianisms go. The rather glaring downside to this is that building it would likely require more resources than exist on Earth, and could make the planet uninhabitable.

Ironically, as much as “disruption” functions as a welcome corrective to systems whose legitimacy seems to rely on the lazy halo of long tradition (which is why, as much as Mark Cuban “just wants to fuck up healthcare”, he can’t) disruption itself draws its legitimacy from the dim first embers of a never-actually-glimpsed future. This is why technical potential sells — it’s the allure of the future that’s so hard to resist — but also why it never really succeeds alone.

It’s the sound of one hand clapping.

Altman’s idea of the singularity is deliberately monumental because it has to be: his is part of a galaxy-engulfing hive mind that no longer knows the outside, a place that has reached peak liquefaction, where the boundaries and distinctions between humans and the technology they use has completely withered away. So we dwell in his synaptic pathways amid wonder and glory forever.

And hope we don’t torch $35 trillion in family health and wealth because of it.

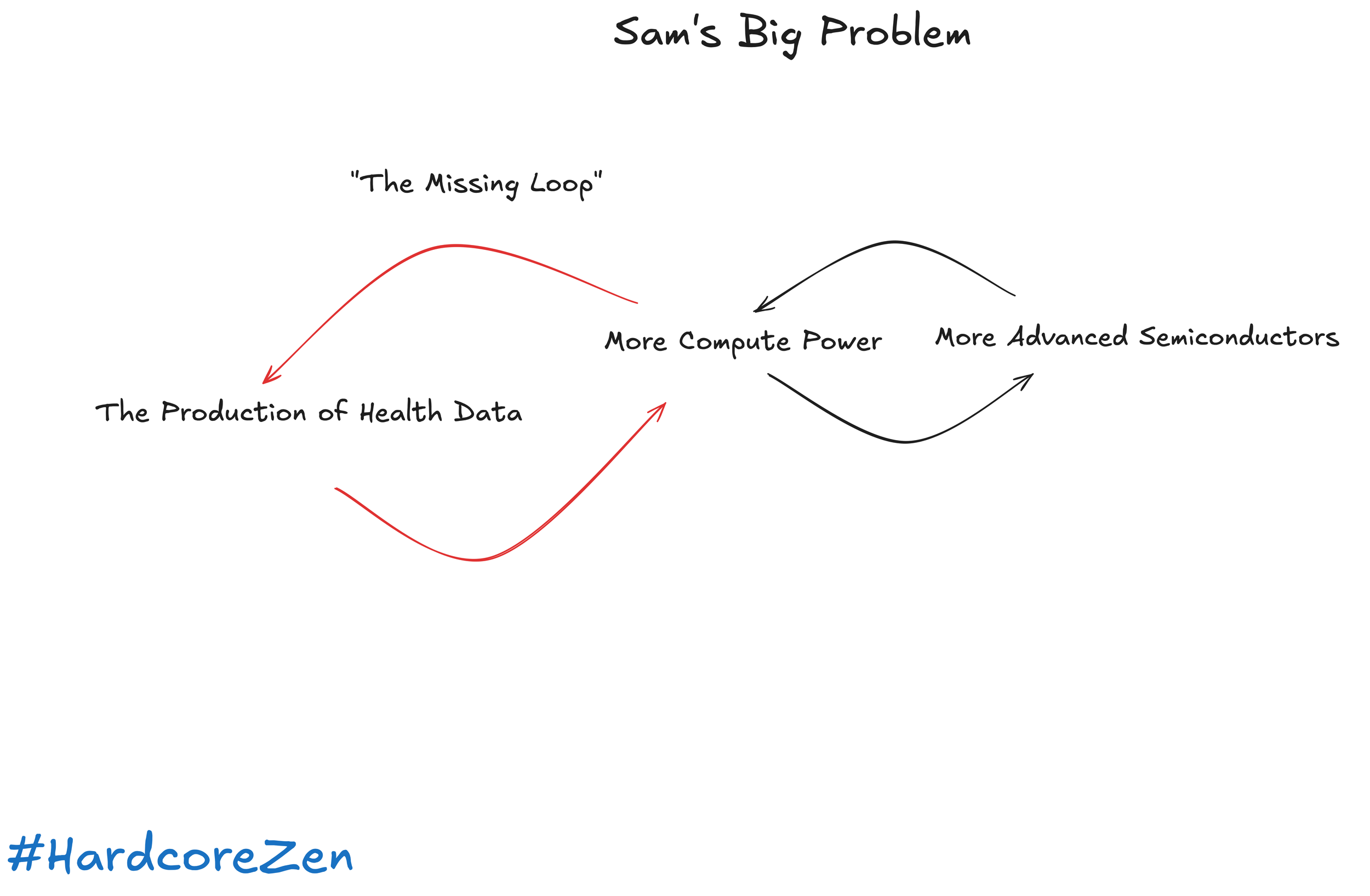

There’s a lot of bullshit in the bubble machine, and I can’t shake my doubts about the near future. A lot of people need a lot of things to go right for the investments to not crash against the shoals of reality (one of those being a market in the production of data). And I also believe that the “AI revenue problem” is really a creative problem, as most strategic problems are. But technology isn’t strategy, which is here big trouble starts.

From Altman’s blog on how to be successful:

“I think the biggest competitive advantage in business — either for a company or for an individual’s career — is long-term thinking with a broad view of how different systems in the world are going to come together.”

In related news, HLTH 2025 wrapped this week.

/ jgs

John G. Singer is Executive Director of Blue Spoon, the global leader in positioning strategy at a system level. Blue Spoon specializes in constructing new industry narratives.