You Can’t “Activist” Your Way Out of System Collapse

Summary: Starboard Value quietly exited Pfizer. Elliott Management's campaign against GSK produced nothing new. Both prove the same point: you can't activist your way out of a structural adjustment in markets ruled by policy, reimbursement, and shifting economic architectures.

The classic story in pharma — the Standard Model — revolves around basic narrative plots, screenplays and templates and lines of dialogue that are recycled again and again in the drug market, regardless of the brand telling them.

These stories may be populated by different settings, characters, and conflicts, but the through lines are:

The Big Short — Badly misreading, misresearching, or just plain mangling the demand environment for a pharmaceutical, which results in forecast misses or sheepish guidance revisions. While the drug market is far from alone in this — see WPP or Nestlé or Pinterest or Verizon, or even Inbound Health (the hospital-at-home startup that had raised over $50 million, shuttered Monday) — the total system collapse of $100 billion “vaccine”/“mRNA” market, once hailed as a new industrial epoch, is the poster child of the slow-motion implosion in real time.

A Slight Case of Overbombing — Carpet bomb the ‘battlespace’ with identical “creative”, roughly $15 billion worth of it in the United States alone. Granted, it’s identical because it has to be; drug promotion sticks with a mandatory formula. First, the uplifting visual vignette: smiling, active people often shot in golden light. Then the machine-gun disclosure of risks. (The sameness isn’t laziness; it’s a legal design pattern that creates a recognizable structure for commercials to inform the public while also protecting the company from liability (and the brand managers from losing their jobs).

The Loop in Time — A meditation on circularity and the recursive recycling of past experience. The narrative thread comes from a song of the same name by Wally Brill that was released on the album Altered Realities in April 1999. Brill is best known for blending technology, voice, and ambient sound design — he tends to build pieces that feel like they exist in a feedback cycle, moments folding back onto themselves, history echoing forward, and past and future collapsing into a single sensory frame. Sort of like the database of case histories from a management consultancy;

Visit McKinseyLand — When things start to feel wobbly, analyze the analysis and then reorganize operations to make the standard model run cheaper or more efficiently, probably through layoffs, automations or other “optimizations”.

Panic at The Disco — Scramble and surprise around the patent cliff and, now, the new dread, having to negotiate price with the United States government as part of the Inflation Reduction Act and MFN. The music is speeding up, the floor is shaking, and everyone knows the next step could be a misstep.

The Exit 9 Problem — Exit 9 is a metaphor for “me too” applications of technology. The title comes from Exit 9 off the New Jersey Turnpike. At the exit is a mixed-use office complex called Tower Center, specifically, One Tower Center and Two Tower Center. HCLTech opened in One Tower Center last June; Wipro, one of its competitors in the $282 billion Indian IT services market, has been there much longer. These are not similar companies. They’re identical.

Nicholas Carr writing in Does IT Matter? : “As managers grapple with these operational, organizational and strategic challenges, they should take particular care to rid themselves of the illusions that new technologies often inspire — and that have been a particular hallmark of what has come to be call the digital age.” In other words, when everyone gets their hands on the same “amazing” technologies, and everyone deploys them in the same “amazing” way, what you end up with isn’t progress but a great flattening, a sea of sameness rolling out to the horizon, awe-inspiring only in its sheer, monotonous scale.

Using artificial intelligence in target identification, molecular design and clinical trials to produce “the next generation of breakthroughs for patients” doesn’t open space for strategic differentiation because it isn’t a unique industry narrative. The aim is still drug production — maybe even a quantum churn of routine cures and diagnostics that can detect disease decades in advance — but without a new economic system built to swallow all those “boring” cures (Zuckerberg’s word, not mine), the whole beautiful engine of AI-powered innovation will just evaporate into the American ether of healthcare dysfunction. It will crash headlong into the old priesthood of utilization management and prior authorization and QALY, that shadow bureaucracy of actuarial tables used legacy payers and benefit brokers that still decide who receives care and who gets the administrative shrug.

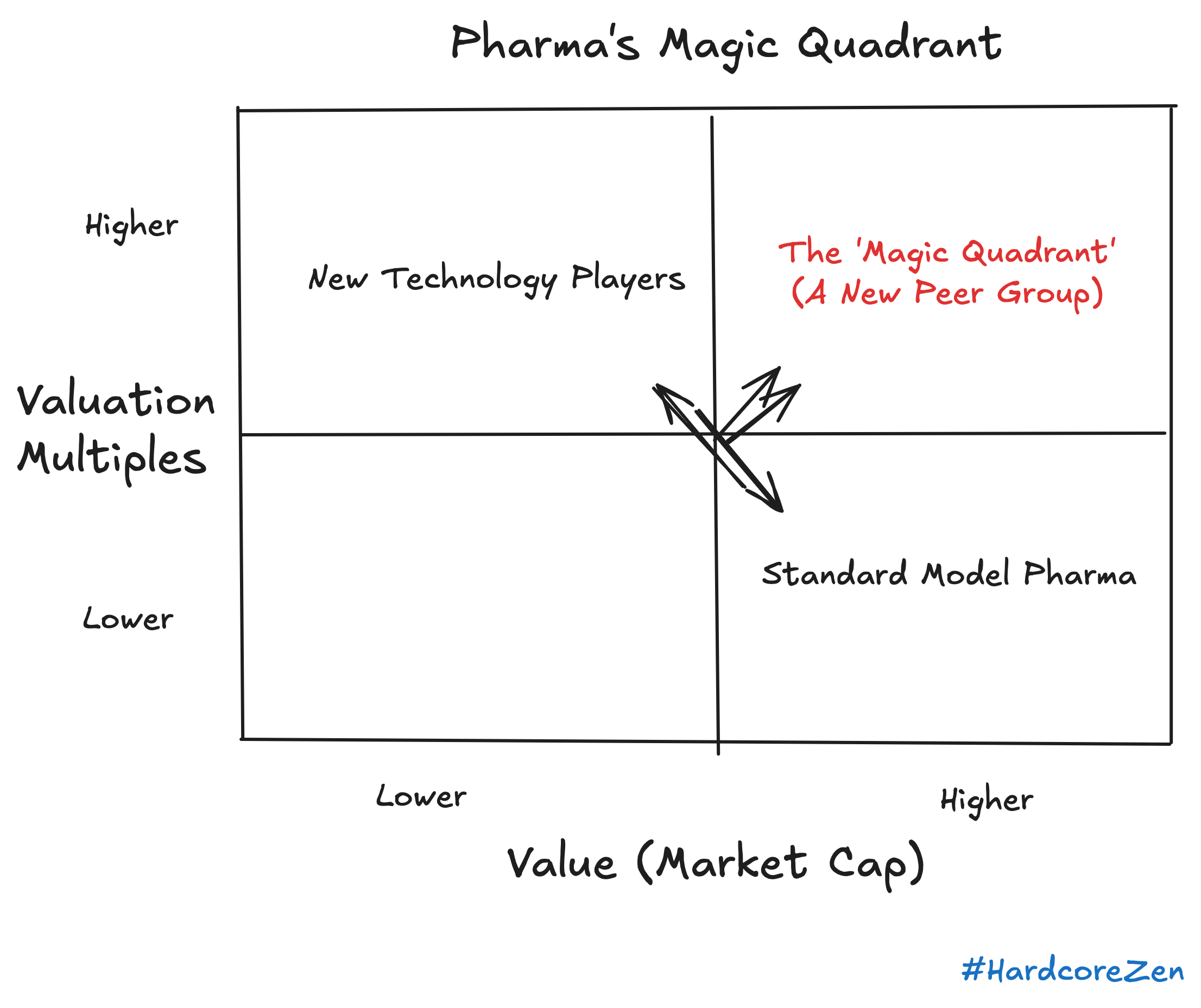

Said another way, pharma is still arranging itself around the Standard Model, a meta-narrative that mistakes scientific achievement (producing technical inputs) for economic innovation. The technical potential of a drug — the TPP, the label copy, the lab-coat catechism — still gets treated as the gravitational center of growth and competition. The industry hasn’t written its way out of its own Main Character Syndrome; it remains trapped inside the story it keeps telling about itself, a storyline where “innovation” is defined, packaged, and telegraphed to The Street like a seasonal offering.

And The Street, in its cold, carnivorous way, obliges. It measures management performance by that same cramped storyline, rewarding the familiar rites and punishing any executive who dares to hint that value might live somewhere outside the lab bench and the quarterly guidance deck.

Cue the activists.

When Markets Disintegrate

Back in July when GSK shared quarterly results that included cutting its forecast for vaccine sales, CEO Emma Walmsley, who fought off pressure from the activist investor Elliott Management for strategic changes, said that “with a best-in-class data profile, we are confident Arexvy [its vaccine for RSV] will return to growth next year and longer term can achieve more than £3 billion in peak year sales.”

She was half-right.

In her final earnings report as CEO in October (Walmsely is stepping down in January, after a “shock” announcement that she is being replaced by GSK chief commercial officer Luke Miels), Arexvy beat consensus by 13%, although its sales growth did not benefit from the U.S. market. Going forward, Walmsley told reporters that GSK is “very cautious about the environment in the U.S.”

As it should be.

And not just for GSK. There is an epidemic of commercial withering across the board for any system of markets whose revenue depends on successfully rotating in an orbit where the word “vaccine” is the Main Character in the screenplay, especially if the center-of-gravity of thought, investment and commercial models is premised on the potential of the United States as a drug market. RFK Jr. is intentionally, methodically dismantling an entire industry ecosystem, in real time.

Demand for flu shots and vaccines is evaporating, falling out of favor in a post-pandemic world. While uptake for flu shots has never been stellar, vaccine fatigue, politics, information overload and boredom, a “miserable pharmacy experience” and lowered public trust are all part of the ‘growth problem’ for these products. (The ‘vaccine market’ is actually a system of markets comprised of a drug market + retail pharmacy market + telehealth market). And all the promotional push in the world, for the products themselves and for the galaxy of disease awareness campaigns the industry funds to create demand, won’t stop The Big Short from happening in “vaccine” sales.

It also isn’t helpful to the forecast when the new ACIP chair compares Covid requirements to the Holocaust, or says the vaccines caused cancer and miscarriages. Or when the director of the Food and Drug Administration’s vaccine division writes a memo that an internal review found that at least 10 children died because of receiving the Covid vaccine. (The 3,000-word memo, obtained by NBC News, was written by Dr. Vinay Prasad, director of the FDA’s Center for BiologicsEvaluation and Research.)

“When we saw this [reduced demand for vaccinations] for the first year …. we were like, ‘OK, it’s just coming out of the pandemic. There’s all these COVID vaccines. This feels like a blip,” said Stefan Merlo, vice president of commercial operations at vaccine maker CSL Seqirus in an interview for Axios last year. “We don’t believe that anymore.”

One could ask: Why did you believe it in the first place?

The Nimble Leap

The map, as they say, is not the territory. The reality problem, the ground truth, is deeper, wider and more complex. Groupthink has become an almost virus-like infection that’s been reproducing itself in all the pathways for decades, self-generating the code for its own survival. An entire form of assessment has become obsolete.

What worked no longer works.

A few weeks ago, Starboard Value quietly exited its stake in Pfizer after attempts to shake things up failed to lift the share price.

Back in late 2024, with Pfizer’s stock about half its pandemic peak, Starboard swooped in, hoping to spark a turnaround by nominating seasoned industry execs and pressuring management. The pressure campaign turned into a circus, with Starboard taking a $1 billion stake. But efforts to bring in outsiders, including former CEO Ian Read, didn’t gain traction, and Pfizer’s valuation slid from $162 billion to $142 billion throughout Starboard’s involvement. Investors kept questioning how Pfizer would grow beyond pandemic-era highs, and with no real progress, Starboard disclosed its exit in a 13-F filing. The move repeats a familiar playbook, as Starboard also recently sold out of Fortrea Holdings after a sharp drop there as well (the shareholder value of Fortrea has dropped nearly 50% since Starboard’s investment became known).

At the time of Starboard’s activism against Pfizer, Starboard when full McKinseyland and published an “extensive slide deck” laying out a detailed technical argument, but containing no actionable ideas, no new strategic concepts, no unique narratives. Starboard’s CEO Jeff Smith only stated “something needs to change” in a vague our-value-is-to-be-valuable-to-shareholders kind of way.

It was the same sort of ectoplasmic generality that shaped Eliott’s logic in its activism against Walmsley, criticizing her performance and leadership, advocating for a shake-up of the board and even demanding that Walmsley reapply for her job. That activism PR campaign started with a press release and nine-page letter sent to Sir Jonathan Symonds and Members of the Board of Directors of GSK; its essence was an analysis of GSK’s past performance and the company’s plans to separate the Consumer Health business from the pharmaceuticals and vaccine business (“New GSK”). The letter set off an exciting flurry of articles in the British press. It was also a confusing one. “It roars out a fire and brimstone sermon” declared Jim Armitage in the Evening Standard who the called it “an excoriating open letter to investors.”

But read it carefully, and you realize most of the sins it catalogs were committed years before Walmsley ever walked through the door. Time delay in feedback loops is the tenth rule of systems theory, and it always has its revenge. Hemingway translated it for the rest of us: strategic collapse comes like bankruptcy, slow for a long while, then all at once, like a match finally hitting dry timber. And when you drill into the supposed substance of what Eliott claims they would do differently, there’s no there there. No heresy, no hard break from the old religion, no magic leap into a new peer group. Just the faint rustle of a man rearranging papers on a desk he has no intention of truly disturbing.

Including this nugget of nothing for GSK’s vaccine business:

Preserve Vaccines and Pharma’s nimbleness

We do not believe Vaccines and Pharma should be fully integrated because we are not convinced that ‘clear synergies’ exist between the two. While there are modest R&D overlaps related to basic immunology research, the Vaccines and Pharma businesses are largely separate in terms of manufacturing processes and commercialisation. GSK should benefit from exchanging views on immune system research and best practices without the need to integrate the two businesses.

Providing Vaccines more autonomy could increase its talent retention and nimbleness, so that it can better capture opportunities such as Shingrix/RSV, and so that Vaccines will be better positioned for future pandemics than it was for Covid-19. Additionally, maintaining separate divisional reporting for Vaccines will allow investors to appropriately value GSK’s crown jewel Vaccines business. To avoid any doubt, Elliott is not recommending a sale of the Vaccines business nor are we recommending any changes that could potentially result in a Vaccines business that will not remain U.K.-owned.

(I wonder if Eliott still believes this?)

The thing that’s not working in the pharmaceutical industry is the same thing that everyone else is struggling with, including Starboard and Eliott: how to ride chaos, how to see with better vision, how to produce better strategy stories.

Starboard’s quiet exits from Pfizer and Fortrea are a perfect case study in the limits of financial activism in a policy-defined market. No one outside the fund knows the exact losses, because 13F filings don’t disclose cost basis, but you don’t need a spreadsheet to understand the shape of the outcome. The moment Starboard stepped into both names, the ground was already shifting under their feet: COVID-era cash flows collapsing at Pfizer, and a post-spin clinical-services story at Fortrea that couldn’t outrun the gravitational pull of disappointing guidance, high leverage, and a sector-wide derating.

The activist playbook assumes that value is unlocked by sharpening operations, tightening capital allocation, or forcing a strategic rethink. But healthcare doesn’t bend to that logic anymore. It bends to Washington, to Medicare negotiation, to GLP-1 economics, to a drug-pricing regime that now functions as industrial policy. Starboard wasn’t wrong on the numbers; they were trapped in the system of which they are a part, a bit player. And when the system moves, the narrative breaks faster than any activist can fix it.

The real lesson isn’t about Starboard at all. It’s that you can’t “activist” your way out of a structural adjustment. In markets ruled by policy, reimbursement, and shifting economic architectures, even the sharpest operators become passengers. Pfizer and Fortrea weren’t failed trades; they were reminders that in modern healthcare, you can buy the stock, but you don’t control the story.

A New Value Pathway

Where extensive slide decks prepared by the PowerPoint Powerhouses tend miss is the framing, the bigger step into a space for strategic imagination: everyone is searching for “fit” to a world where all the usual landmarks have disappeared. Everyone. Where things are going off the rails is in the title slide, the headline in the press release: “healthcare” is not investing enough intellectual and creative energy positioning the objective that gives direction to the strategic direction. There is no voltage of the different to spark the new.

What’s needed, then, is originality, a market-maximization theory to replace the profit-maximization one that dominates and eviscerates and is now determining the fates of hundreds of millions of people in the United States alone. And that new market theory needs patience by Wall Street to prove it out. When it comes to big system change — vision and strategy to shape the ‘next hundred billion’ in growth from the largest and most lucrative market on Earth — the roadmap doesn’t start with the conventional frame, the journey doesn’t start alone, and the ‘impact horizon’ should extend beyond three years. It starts with vision to construct a new industry ecosystem in an organized and persistent way. Think GSK + Clear + Dubai International Airport working as a single organism, one system of markets collaborating to construct what Elliott said it wants from GSK: a new “value-maximising pathway” for the vaccine business.

Healthcare is an N-sided market. Recombination is where the novel action is.

The thing this moment needs “activism” around is a new orbit for economic competition, a different strategic physics, where market maximization happens through new economic systems competing against each other for ‘the production of affordable health’.

Eliott had the view that GSK should be salvaged from what it called “years of under-management”; Starboard felt that“something material” needed changing at Pfizer. But if you follow that logic, the “management” of a $5 trillion system of markets fails every year. For drug manufacturers — and activist investors like Starboard — the elephant in the room is the room itself, an approach to business and product marketing unchanged sine the “modern pharmaceutical industry” began around 1849, when Pfizer was founded in Brooklyn.

Competitive convergence is born from strategic atrophy.

It’s a ‘category problem’ where competitors produce and promote indistinguishable offerings with identical storylines of value, use identical business models, and share mental maps of how ‘the market’ works, or should work. Companies (and even governments) stop competing on strategy and start competing on operational equivalence. Ultimately competitive convergence is a sign of leadership not dealing with ‘contextual collapse’ — it produces painful, recurring and expensive lessons in how hard the Invisible Hand can slap.

Still, Elliott and Starboard prove the bigger point, at least in healthcare: there are so many actors and so little action.

/ jgs

John G. Singer is the executive director of Blue Spoon, the global leader in positioning strategy at a system level. He works with organizations to design new market narratives and exit strategies from collapsing systems.

He is the author of When Burning Man Comes to Washington: A Field Manual for Riding Chaos, which introduces Hardcore Zen, a unique method for leading system-level change. His latest work, The Burning Man Index™, scores 27 institutions on their proximity to narrative collapse — the moment an organization's story stops matching the world it operates in.

To explore a Hardcore Zen whiteboard or arrange a guest lecture, email here.